Mpox is in the news again. In July 2022, an outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) spread to several countries, including the U.S., prompting the World Health Organization (WHO) to designate it a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). As cases declined in May 2023, the public health emergency label was lifted.

But now, experts say the problem is back, and more concerning than before.1 On August 14, 2024, The WHO announced that Mpox had again become a PHEIC. During the announcement, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, PhD, the Director-General of WHO, said, “The emergence of a new clade of Mpox, its rapid spread in eastern DRC [Democratic Republic of Congo], and the reporting of cases in several neighboring countries are very worrying. On top of outbreaks of other Mpox clades in DRC and other countries in Africa, it’s clear that a coordinated international response is needed to stop these outbreaks and save lives.”

The new “clade” he refers to is a strain that appears to be deadlier than the form of Mpox that spread in 2022-2023.

It’s important to take precautions and seek out testing and care if you or someone close to you shows signs of having been exposed to Mpox. Here’s what you need to know.

What Is Mpox?

Mpox is a viral disease related to smallpox, which causes pus-filled lesions on the skin along with fever, pain, chills and exhaustion.2

The main difference between the two diseases is that smallpox tends to be more severe, but mpox causes your lymph nodes to swell, which doesn’t happen with smallpox.

Mpox is endemic to Africa, though small outbreaks, usually among people who have recently traveled to the continent, have happened before.

How Is Mpox Spread?

The term “monkeypox” is a bit of a misnomer. Scientists first observed the disease in monkeys in 1958, but they now think rodents are more likely to carry the virus and transmit it to humans through bites or scratches. Between humans, the disease can spread through direct physical contact or touching surfaces or clothing that comes in contact with an infected individual’s sores. Close contact includes sexual activity, but also other types of contact like cuddling and dancing.3

Before 2022, there had been previous outbreaks of mpox outside of Africa, but were all short-lived.4 Usually, an individual had traveled to Africa right before developing symptoms. One of the most notable outbreaks, in 2003, was caused by prairie dogs that had been stored near small mammals from Ghana. In that outbreak, 47 cases of the disease in humans were reported across six states. If a person can isolate themselves when they develop symptoms, they can avoid spreading the disease to others.

The reason scientists were concerned in 2022 and 2023 was that cases are showing up in countries all over the world, all at once. We’re seeing a similar outbreak, with more cases happening in the summer of 2024.

How Was the 2022-2023 Mpox Outbreak Different from Previous Mpox Outbreaks?

Previous outbreaks have caused painful rashes that cover large portions of the body and often start on the face, hands and feet. “All patients in the current US Mpox outbreak in 2022 have experienced a rash, but the lesions have been scattered or localized to a specific body site,” explained Inger Daimon, MD, PhD, director of CDC’s Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology (DHCPP) in a June 21, 2022 briefing. In several cases, those body sites have been the genitals or anus, causing the disease to appear similar to sexually transmitted infections like herpes.

Many patients in 2022 and 2023 have experienced mild fever or body aches or sometimes even no symptoms prior to developing the rash.

What’s New About Mpox in 2024? Is Mpox Deadly?

Mpox is not only spreading faster in 2024 than it did before, but it appears to be more deadly. There are two main clades, or strains, of Mpox: Clade 1 and Clade 2, each with its own subvariants. In 2022-2023, Clade 2 was dominant. Clade 2 typically kills less than 0.1% of people infected. But now, Clade 1 is dominant, and it can kill up to 10% of those infected.5

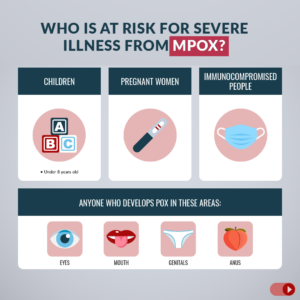

Who Is at Risk?

In previous outbreaks, children have often been the main ones to contract the virus. In 2022-2023, the outbreak seems to be concentrated in adult men who report having sex with other men, though some women have also tested positive for the disease. The virus is spread by close contact, but not exclusively sexual contact, with infected individuals.

On Sept 15, 2022, Demetre Daskalakis, MD, PhD, White House Mpox Response Deputy Coordinator, told media at a press conference that “our data tells us that Mpox is not an infection that exists in isolation. It travels with HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. An MMWR [morbidity and mortality weekly report] published last week,6 tells us that 61% of people diagnosed with Mpox either had HIV or an STI.”

Salim Abdool Karim, MD, PhD, Chair of the Africa CDC Emergency Consultative Group (ECG) repeated that concern on August 13, 2024 “It’s clear that we’re facing a different scenario with far more cases, resulting in a higher burden of illness,” he said. “Our concern is that we may be seeing more fatalities in Africa due to the association with HIV,” he noted.

But it’s not just these patients who are vulnerable. While the most recent outbreak was spread largely through sexual contact, the 2024 outbreak is affecting children most acutely. Experts believe this may be due to weaker immune systems of those under age 15 and close physical contact through school and play. The 2024 outbreak is concentrated among children: 67% of cases and 83% of deaths occurred in children under the age of 15.7

Are There Any Treatments?

No treatments have been developed specifically for mpox, however, the FDA has permitted compassionate use of several antiviral medications if a mpox outbreak occurs. Those treatments include:8

- TPOXX (tecovirimat), an antiviral pill or injection originally approved to treat smallpox in both children and adults. It blocks a protein that smallpox and mpox both need to spread from cell to cell. This treatment was approved by the FDA for smallpox through the “animal rule,” because it wouldn’t have been possible to conduct clinical trials in humans.9 The drug’s efficacy was tested on monkeys with mpox, and the safety was assessed in human trials. A phase 3 clinical trial is ongoing, and will include children along with people who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Since the start of the outbreak, the drug has been given to 6,932 individuals with Mpox. The National Institutes of Health published a summary of a trial in DRC on August 15, 2024 that suggested that TPOXX did not improve outcomes for patients with Mpox, but that quality supportive care (such as hydration and treatment of secondary infections) did reduce fatalities from 3.6% to 1.7%. The larger U.S. trial is still ongoing.10

- Vistide (cidofovir), an antiviral designed to treat cytomegalovirus (CMV) in patients with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) by preventing the virus from replicating. In patients with healthy immune systems, CMV rarely causes symptoms or illness, but it can be dangerous for patients with compromised immune systems, such as those with HIV.11

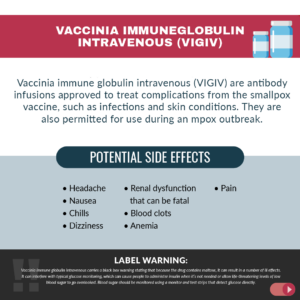

Mpox Vaccine - Vaccinia immune globulin intravenous (VIGIV) are antibody infusions approved to treat complications from the smallpox vaccine, such as infections and skin conditions. They are also permitted for use during a mpox outbreak.12

- Tembexa (brincidofovir) was approved by the FDA in June 2021 to treat smallpox. It is incorporated into the viral DNA to slow its replication. The CDC hopes to make it available as a mpox treatment, but it does not currently have the authorization or an available stockpile.

What are the Side Effects of Medications Available to Be Used for Mpox?

Side effects of tecovirimat13

The drug is generally well-tolerated, but you can experience:

- Headache

- Nausea, vomiting or diarrhea

- Pain

- Fever

- Chills

- Depression or irritability

- Abnormal heart rhythms

Warnings about Vistide, cidofovir14

Cidofovir’s label carries a black box warning that the drug can cause kidney impairment, which may be fatal. It may also lead to birth defects, cancer and impaired fertility.

Other occasional side effects of cidofovir include:

- Blurry vision

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fever

- Infections

- Difficulty breathing

- Weakness and fatigue

- Headache

- Rash

- Hair loss

- Anemia

- Pain

- Chills

- Reduced white blood cell counts, which can leave you vulnerable to infections.

Warnings about vaccinia immune globulin intravenous:15

Vaccinia immune globulin intravenous carries a black box warning stating that because the drug contains maltose, it can result in a number of ill effects. It can interfere with typical glucose monitoring, which can cause people to administer insulin when it’s not needed or allow life-threatening levels of low blood sugar to go overlooked. Blood sugar should be monitored using a monitor and test strips that detect glucose directly.

Other occasional side effects of vaccinia immune globulin intravenous include:

- Headache

- Nausea

- Chills

- Dizziness

- Renal dysfunction that can be fatal

- Blood clots

- Anemia

- Pain

Warnings about brincidofovir:

Brincidofovir’s label contains a warning that when the drug was tested for a disease other than smallpox in a clinical trial lasting 24 weeks, patients who took the drug were more likely to die than those who were given a placebo. This outcome didn’t happen in shorter trials for smallpox.

The drug may also cause birth defects and cancer. People who can become pregnant should use contraception for at least two months after taking their final dose. People whose partners can become pregnant should use condoms for at least four months after their last dose. Brincidofovir may also permanently impair fertility.

Other potential side effects of brincidofovir include:

- Liver damage

- Diarrhea and vomiting

- Abdominal pain

How Can I Avoid Getting Mpox?

Anyone who develops symptoms of Mpox should isolate and report their symptoms to their physician. Avoid contact with anyone in your household who may have the illness and consider wearing a face mask at home, since it’s possible that the virus could spread through respiratory droplets. The virus can incubate in your body for a week or more before causing symptoms, so if you suspect you may have been exposed, avoid contact with others even if you don’t have symptoms.

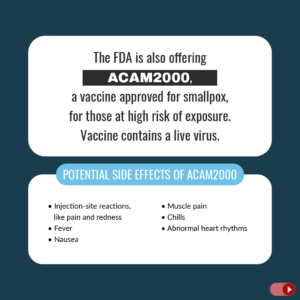

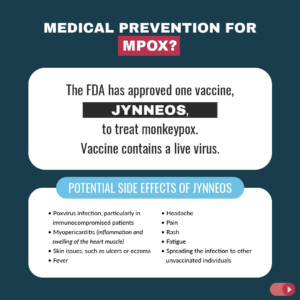

Additionally, the FDA has authorized one vaccine, Jynneos, to prevent Mpox and is also offering ACAM2000, a vaccine approved for smallpox, for those at high risk of exposure. Both vaccines contain a live virus. While ACAM2000 is capable of replicating in your body, Jynneos is not, so it won’t cause an infection in immunocompromised patients.16

Patients take Jynneos in two doses, 28 days apart. They don’t get their highest level of protection until two weeks after the second dose. ACAM2000, on the other hand, is a single-dose vaccine that provides peak protection after 28 days.

A full course (2 shots) of the Jynneos vaccine is 66-86% effective in preventing illness.17 A single shot is 36-75% protective. In the few instances in which fully vaccinated individuals contracted Mpox, their diseases were mild, suggesting that the shots also protect against severe illness, according to a report from the CDC, which also suggested that immunity remains strong through May 2024.18 If you got both shots in 2022, you do not yet need a booster.

Who Should Get a Mpox Vaccine?

“The vaccines are really limited to healthy adults,” explained Pekosz, the virologist and co-director of Johns Hopkins Center of Excellence for Influenza Research and Response on Sept 8, 2022. “There’s been very little testing of this vaccine in populations outside of healthy adults.” He says it’s unlikely that vaccination against the disease would be recommended for anyone other than healthy adults, outside of extreme circumstances.

The CDC recommends the vaccine for people at high risk of Mpox exposure. That includes:

- People with a known or suspected exposure to someone with mpox

- People with a sex partner in the past 2 weeks who was diagnosed with mpox

- People who identify as a gay, bisexual, or other man who has sex with men or a transgender, nonbinary, or gender-diverse person who in the past 6 months has had any of the following:

- A new diagnosis of one or more sexually transmitted diseases (e.g., chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis)

- More than one sex partner

- People who have had any of the following in the past 6 months:

- Sex at a commercial sex venue (like a sex club or bathhouse)

- Sex related to a large commercial event or in a geographic area (city or county for example) where mpox virus transmission is occurring

- People with a sex partner with any of the above risks

- People who anticipate experiencing any of the above scenarios

- People who are at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses (e.g., certain people who work in a laboratory or a healthcare facility).

As of January 2024, the majority of vaccine recipients in the U.S. have been men between the ages of 25 and 39 years old.19 However, in some cases, the vaccine has been given to children and infants over 6 months of age to prevent disease after they’d been exposed to Mpox.20

What Are the Side Effects of the Mpox Vaccines?

Side effects of ACAM2000:21

- Poxvirus infection, particularly in immunocompromised patients

- Myopericarditis (inflammation and swelling of the heart muscle)

- Skin issues, such as ulcers or eczema

- Fever

- Headache

- Pain

- Rash

- Fatigue

- Spreading the infection to other unvaccinated individuals

Side effects of Jynneos:22

- Injection-site reactions, like pain and redness

- Fever

- Nausea

- Muscle pain

- Chills

- Abnormal heart rhythms

The CDC specifies that people who received the Jynneos vaccine intradermally had less pain after.23 However, they did experience more swelling, redness, itchiness, and skin thickening which can last several weeks. This reaction is common, and can look like a single red bump around the injection site.24 You can ask to get the vaccine injected into the fat layer on the back of your upper arm instead, if you prefer. The vaccine is equally effective delivered both ways.

Are the Mpox Vaccines Safe for Pregnant People?

There isn’t enough data on Jynneos in humans to determine its safety in pregnant populations, but animal studies have not found any increased risk of birth defects or miscarriages in those that received the vaccine while pregnant.25