The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has now approved the diabetes drug Wegovy (semaglutide), previously okayed for diabetes, for weight loss. I wonder why? I was the consumer representative on the FDA advisory panel that voted to approve Wegovy (semaglutide) for diabetes. I voted for it reluctantly and only because the drug helped slightly improve life for those with diabetes.

A small weight loss is one benefit of Wegovy. Patients given Wegovy in clinical trials lost between five and ten pounds. That’s helpful for a person with type-2 diabetes, but for the average person, it is a minor change in body weight. Most overweight people need to lose weight at a far higher rate to become healthier or avoid risks of medical conditions.

Wegovy weight loss is a side effect. Those who should not take Wegovy seem to be causing medication shortages for those that should.

The average weight of an American man is 199 pounds, women are 171 pounds. Experts tell me a weight loss, even that small, can improve the health of people with diabetes. But for everyone else, what is the difference between 199 and 189 or 171 and 166 pounds? Weight related medical problems are not likely to change much with a loss of just a few pounds.

The side effects of Wegovy are very scary and, in my opinion, would outweigh the benefits of someone taking the Wegovy shot just for such minor weight loss. Below are my blog and thoughts when the FDA approved Wegovy in 2017 for diabetes. I have even more concerns now.

In short, those seeking to focus on weight management need far more lifestyle change than the Wegovy medication offers.

(2017) A Trail of Clues to a New Diabetes Drug

Last week, I sat on an FDA panel as the lone consumer rep to discuss and vote on an application for a diabetes drug, semaglutide, from Novo Nordisk. This is a new entry in the category of GLP-1 agonists, six of which are already approved for use in diabetes.

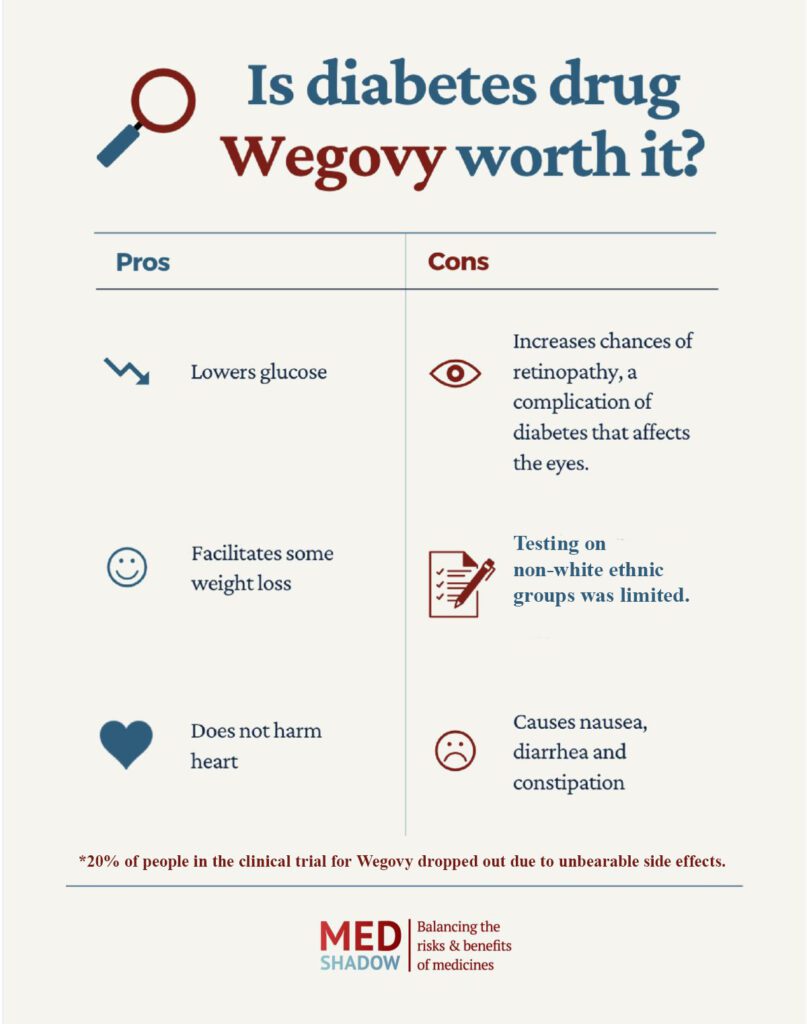

The benefits are clear and strong: semaglutide lowers glucose levels and helps patients drop weight by [what I thought at the time was] a significant level, five to 10 pounds on average. Lowering glucose levels is the surrogate marker that the FDA uses to measure the benefits of new diabetes drugs. The FDA allows surrogate markers because waiting to prove or disprove that a drug lengthens or improves the lives of diabetics would take decades.

However, the side effects are pretty bad. At least 20% of the trial participants had to drop out because they couldn’t take the nausea, diarrhea and constipation. (This is a problem with other GLP-1 agonists, too.) These symptoms could lead to using drugs for side effects. At least one doctor on the panel voiced the obvious: with so much gastric distress, no wonder patients lost weight.

The primary killer of people suffering with diabetes is CVD (cardiovascular disease). https://www.cdc.gov/features/diabetes-heart-disease/index.html The FDA looks closely at the effects of any diabetes drug that could impact CVD. For that reason, in addition to five other clinical trials, Novo Nordisk ran a two-year trial called SUSTAIN 6 that focused on CVD, with a secondary consideration on diabetic retinopathy, a problem that blinds half of all diabetics.

SUSTAIN 6 had mixed results. Happily, it showed a significant decrease in most of the CVD measurements. Compared to the placebo and to comparator drugs, those taking semaglutide had substantially lower rates of non-fatal MI (myocardial infarction, or heart attack), non-fatal stroke, revascularization (needed surgery for bypass or other heart vascular issue) or hospitalization for an unstable angina (poor blood flow to heart).

Unfortunately, data also showed semaglutide slightly increased the risk of being hospitalized for heart failure and had about the same risk (as compared to a placebo) of a cardiac death. Deaths from all causes were about the same as with a placebo. On balance, the drops were significant and the increases small.

Of concern was that diabetic retinitis showed a definite increase among users of semaglutide compared to the placebo. In tests of other GLP-1 agonist drugs, this same pattern had been shown and named “Early Worsening.” In years three and four, the rapid onset slowed, and soon the placebo group’s retinitis symptoms increased well past the tested drug group. However, Novo Nordisk didn’t continue the test to prove or disprove that this drug, semaglutide, would follow the same pattern. In addition, the quality of the research conducted on retinopathy wasn’t good. The preferred tests for retinopathy were not conducted and the data collection was inconsistent. We can hope, but cannot assume, the rapid increase in retinopathy that semaglutide causes will level off. Therefore, the doctors on the panel agreed that retinitis progression at a rapid rate is a real possibility.

The eye doctors on the panel discussed and assured the rest of us that there were many procedures for doctors to slow retinitis, and, in their opinion, this was a manageable problem. The greater concern to diabetics, they all agreed, was CV risk, where semaglutide showed a clear benefit.

The above issues I had to leave to the experts. These doctors were trained in medical research and statistics. However, I know that the population upon which a drug is tested must reasonably compare to the population that will likely use the drug. Diabetes is much more common among the non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic populations. Yet the trial participants were 80% white (with the exception of the two trials that were conducted in Japan).

The appropriate patient population is just as important as correct dosing and timing. I was the first panelist to raise this question, and only one doctor added his concern to mine. He abstained from voting yes or no. I wish I’d thought of abstaining as an option. I voted yes, but I remain very worried. Here are my remarks to the committee (lightly edited for clarity):

“Semaglutide does show a lowering of glycemic levels and body weight. It doesn’t seem to cause hypoglycemia as often as its comparator drugs [the drugs to which semaglutide was tested against]. The committee has convinced me that retinopathy is manageable and that the lack of CV harm is a greater benefit. It has significant side effects and adverse events that cause a large percent of patients to stop using the drug.

“I am concerned about the race and ethnic makeup of the trial participants and the lack of subgroup analysis. Black non-Hispanics have the second-highest rate of diabetes, but are so underrepresented in these trials that the actual black patients number in the low 100s.

“The lack of significant subgroup analysis also concerns me. With such small samples it is impossible to know if it has differing effects and safety among women or ethnic groups.

“Considering the commonality of retinopathy with diabetes, it is surprising to me that the research was not gathered in a standardized method and which made it not of the best quality. The applicant seems to be depending on other studies of other drugs to conclude that the “Early Worsening” of retinopathy shown in their trials is temporary and that there will ultimately be a benefit to the patient. If semaglutide follows the pattern of other diabetes drugs, continuing the study for only one more year would have confirmed a pattern similar to other drugs. As it stands, the study stopped at two years, which doesn’t allow any confirmation of benefit.

“The trial was particularly overwhelmingly white. Cardiovascular disease is the Number One killer of women, and it’s very high on the list of cause of death for black people; diabetes has a higher incidence rate in blacks and Hispanics, and they’re not well represented.

“History has shown that drugs tested on only one ethnic group or one sex can sometimes have surprising, and detrimental, effects on subgroups.

“The lack of ability to do subgroup analysis concerns me. I’m going to feel pretty bad if we don’t go on record saying there should be more trial participants, and the trial should reflect the people who need the drug.

“I strongly recommend further study with better demographic representation that allows subgroup analysis to determine efficacy with blacks, Hispanics, women, etc.

“We also need further tracking to find out about the long-term effect on retinopathy.

“I think these further studies should be required, because the public has the right to full safety information.”