Diethylstilbestrol (DES), a drug given to pregnant women in hopes of preventing preterm births (it doesn’t work) was the first synthetic substance proven to be an endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC) 50 years ago. EDCs stay in our body and accumulate which increases their effect on us.  In 2016, the Environmental Protection Agency suggested that if your drinking water had less than 70 parts per trillion of per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS, a known type of EDC), you were likely to be safe from its ill effects. However, on June 15, 2022, the EPA lowered that limit dramatically, suggesting that over a lifetime, even very minute exposures can be harmful. Unfortunately, while manufacturers have phased out many PFAS, they are often referred to as “forever chemicals” because they do not degrade in the environment. Additionally, researchers are frequently identifying new EDCs in products many of us use every day.

In 2016, the Environmental Protection Agency suggested that if your drinking water had less than 70 parts per trillion of per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS, a known type of EDC), you were likely to be safe from its ill effects. However, on June 15, 2022, the EPA lowered that limit dramatically, suggesting that over a lifetime, even very minute exposures can be harmful. Unfortunately, while manufacturers have phased out many PFAS, they are often referred to as “forever chemicals” because they do not degrade in the environment. Additionally, researchers are frequently identifying new EDCs in products many of us use every day.

Even something as simple as defogging your eyeglasses with anti-fog products may be exposing you to endocrine-disrupting chemicals you’d rather avoid, according to a study published in January in the journal Environmental Science and Technology.

PFAS is a group of more than 5,000 chemicals that scientists have only begun to scratch the surface of understanding despite their widespread use in a wide range of products.

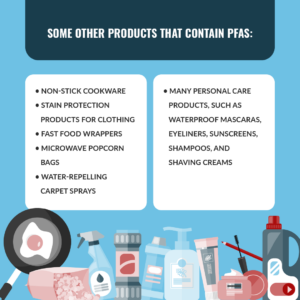

Some Products That Contain PFAS

- Non-stick cookware

- Stain protection products for clothing

- Fast food wrappers

- Microwave popcorn bags

- Water-repelling carpet sprays

- Many personal care products, such as waterproof mascaras, eyeliners, sunscreens, shampoos, and shaving creams

The Environmental Science and Technology study focused on two different PFAS compounds: fluorotelomer alcohols (FTOHs) and fluorotelomer ethoxylates (FTEOs). Very little data exists about these two groups, but since other PFAS are known to cause adverse effects, it’s likely these do as well. Therefore, even though researchers don’t have a lot of information specifically about the PFAS compounds in this study, it’s reasonable to take precautions.

The study found FTOHs and FTEOs in all nine products they tested: four top-rated anti-fog sprays and five anti-fog cloths. The concentration levels ranged widely, from 190 to 20,700 parts per 0.03 fluid ounces of the sprays, and from 44,200 to 131,500 parts per 0.04 ounces of cloth. Again, though, researchers don’t know what doses (if any) of these compounds might contribute to health problems.

So if you don’t know which anti-fog products have high or low levels of these chemicals, and we don’t know what doses might lead to health problems over time, why are we telling you about this study?

We want to emphasize what the DES community has unfortunately realized for a long time: endocrine-disrupting chemicals are all around us and don’t have nearly the regulation they should. When simply defogging your glasses is a potential source of exposure, many other everyday activities probably are too.

Frustratingly, the Environmental Protection Agency doesn’t require polluters, such as manufacturers making products containing PFAS, to notify communities when PFAS remain in the environment. The EPA’s rules on manufacturing with PFAS also don’t require listing them as an ingredient if they’re in low levels or are simply byproducts of the manufacturing.

That means we have only two ways of fighting back: reducing our own use of products containing PFAS when possible, and contacting elected representatives to pressure them to support legislation that would better regulate PFAS in manufacturing.

You can’t live your life trying to avoid every synthetic chemical—it’s literally impossible unless you’re living off the land in a cave. Even then it’s not a guarantee since these compounds stick around for a long, long time. PFAS don’t break down in the environment, and they can last for decades in both the environment and your body.

In fact, the CDC has already found that about 95% of the US population has four specific PFAS in their bodies: PFOS, PFOA, perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA).

So how do you reasonably reduce your exposure to the worst of the PFAS group of compounds without becoming paranoid about every possible source?

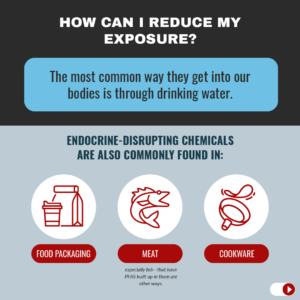

How can I reduce my exposure?

Despite all the products they’re found in, the most common way they get into our bodies is through drinking water. But food packaging, cookware, and eating animals—especially fish—that have PFAS built up in them are other ways.

There’s no value in obsessing over every possible exposure because it causes anxiety, perhaps needlessly if the particular PFAS in some products do end up being less harmful than what we know about PFOS and PFOA.

At the end of the day, you can only reduce your exposure so much, but we also know, as with endocrine-disrupting chemicals, that dose and cumulative exposure make a difference. Each small change you make may help.

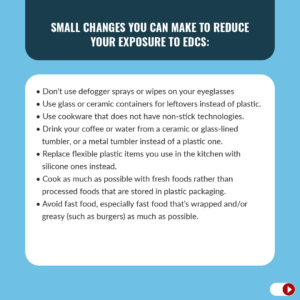

Small changes you can make to reduce your exposure to EDCs:

- Don’t use defogger sprays or wipes on your eyeglasses

- Use glass or ceramic containers for leftovers instead of plastic.

- Use cookware that does not have non-stick technologies.

- Drink your coffee or water from a ceramic- or glass-lined tumbler or a metal tumbler instead of a plastic one.

- Replace flexible plastic items you use in the kitchen with silicone ones instead.

- Cook as much as possible with fresh foods rather than processed foods that are stored in plastic packaging.

- Avoid fast food, especially fast food that’s wrapped and/or greasy (such as burgers) as much as possible.

- Use waterproof materials and products as little as possible, particularly in cosmetics and other personal care products. Product labels that list “fluoro” in the ingredients have PFAS in them. (Even some dental floss contains PFAS, though, again, we don’t know if they’re harmful or how much.)

- If you do go for fast food, seek out the places that have pledged to remove PFAS from their food packaging. You can search for these places online. (MedShadow does not endorse particular stores or restaurants, and the list will continue to change, so we’re not including any lists here.)