It’s been 16 years since the first vaccine designed to prevent cervical cancer received approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine was first approved and recommended for females who were ages 9 to 26 years old. The recommendation was limited to females because the vaccine’s original FDA approval was for prevention of genital warts and cervical cancer, since HPV, a sexually transmitted infection, causes more than 90% of all cervical cancer. Once additional studies confirmed other cancers caused by HPV and the viral strains most often responsible, researchers updated the vaccine to protect against additional strains of the virus and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has expanded recommendations to males and to age 45.

Today’s HPV vaccine, Gardasil-9 (Human Papillomavirus 9-valent Vaccine, Recombinant), prevents infection against nine strains of a virus that can cause six different kinds of cancer, and a number of studies have shown a reduction in both HPV infections and in cervical cancer cases since the vaccine’s introduction. Yet many people may have questions about the vaccine’s risks and benefits, whether they are considering getting the vaccine themselves or deciding whether to accept a doctor’s recommendation to vaccinate their child.

More than half of all teens ages 13 to 17 are fully vaccinated against HPV, and 72% have received at least one dose of the vaccine, according to the CDC’s most recent statistics. Although HPV vaccination rates have been increasing among adolescents since its introduction, the rates still lag behind other vaccines given in adolescence, including the meningitis (MenACWY) vaccine Nimenrix (meningococcal polysaccharide groups A, C, W-135 and Y conjugate) and the Tdap vaccine against tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis (whooping cough).

Why the lag? The HPV vaccine got off to a rocky start, with some parents questioning why it was necessary to vaccinate their children against a disease that’s primarily transmitted sexually. Others worried about side effects of HPV vaccination or have heard concerning stories about health problems following the shot. Many misconceptions exist about the HPV vaccine, and it can be difficult to separate the misinformation from the truth about the vaccine’s safety and effectiveness.

According to Robert A. Bednarczyk, an assistant professor of global health and epidemiology at Emory University’s Vaccine Center and Rollins School of Public Health, researchers have found the most common reasons for not getting the HPV vaccine are safety concerns, not having the vaccine recommended to them by a doctor, not believing the vaccine is necessary, and not knowing enough about the vaccine. This article will address why the vaccine is recommended, its safety record is and what people need to know about the vaccine in general.

Understanding HPV

More than 150 strains of HPV can infect people, but the vast majority of them cause no symptoms and go away on their own. Nearly all HPV transmission occurs during sexual contact, with or without intercourse, but it’s possible to transmit HPV without sexual contact, such as through deep kissing when one person has an active infection with open sores or, in rare cases, by sharing underwear or swim wear. Because HPV is so common, nearly everyone who is sexually active will probably contract the virus at some point. In fact, the CDC reports that around 43 million people had HPV in 2018, though that’s substantially lower than the 79 million reported to have it in 2013. But nearly all these people also won’t know it and won’t ever develop cancer as a result.

The problem is that around 40 types of HPV can cause genital warts or different types of cancer, including cervical, oropharyngeal (throat), anal, penile, vaginal and vulvar cancer. Scientists have identified which strains are responsible for the bulk of these health problems.

Of the 14 high-risk types of HPV, four were included in Gardasil, the vaccine developed by Merck and approved in 2006: HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18. While HPV 6 and 11 are responsible for most genital warts caused by the virus, HPV 16 and 18 are responsible for about 70% of all cervical cancers. HPV 16 also causes the majority of oral and throat cancers in the US and contributes to anal, penile, vaginal and vulvar cancers. HPV 18 can cause some of these cancers as well, though not as many as HPV 16.

Then in 2014, the FDA approved an updated vaccine, Gardasil-9, which protected against five more strains besides the original four: 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58, which are responsible for 20% of all cervical cancers. Some of these also contribute to the other types of cancer, such as HPV 33 causing some vulvar cancer. The FDA also approved Cervarix (Human Papillomavirus Bivalent (Types 16 and 18) Vaccine, Recombinant), a vaccine targeting only HPV 16 and HPV 18, in 2009. Its manufacturer, GlaxoSmithKline, pulled the vaccine off the market in 2016 because it could not compete against the Merck vaccines that protected against more strains. (The side effects of Cervarix were similar to those of Gardasil.)

Who Is Recommended to Get the HPV Vaccine

The vaccine is recommended for males and females ages 9 to 16 and is most commonly bundled in doctor visits with the meningitis and Tdap vaccines given starting around age 11. While this age feels very young for vaccination against a sexually transmitted infection to many parents, that’s also the point: the vaccine is most effective when given before someone begins engaging in sexual activity. Most people are exposed to at least one strain of HPV within two to five years after first having sex. Therefore, if the recommendation were made for the whole population at an older age, such as the late teens, there would be many people who have already begun sexual activity and would not get as much protection. For example, more than half of all teens have had sex by the time they turn 18, according to the CDC. The average age of first intercourse is 16 among males and 17 among females in the US, according to the Kinsey Institute. Even if your child doesn’t have sex until an older age, the CDC must make recommendations for the whole population and take into account risks such as sexual assault, which can occur at earlier ages and, obviously, without a minor’s consent.

Independent of when people first begin having sex, however, research has also shown that the immune system responds more efficiently to the vaccine when it’s given at a younger age. That is, the body produces more antibodies against HPV when people receive it in earlier rather than later adolescence. For this reason, only two doses of the vaccine are recommended for anyone who receives the first dose between ages 9 and 14. Those who receive the first dose at age 15 or older should get three doses to ensure their immune system produces enough antibodies for the vaccine to be effective.

Until 2018, only those up to age 26 were recommended to receive the HPV vaccine, but the CDC expanded who has access to the vaccine when new evidence revealed that it may have benefits in older men and women. After the FDA approved Gardasil 9 for women and men ages 27 to 45 in October 2018, the CDC recommended shared clinical decision-making for this age group.

“Basically, you talk with your doctor about your perceptions of your risk and risk factors and where you’re at in your life and what’s going on, and then make that decision about whether it’s in your best interest to get vaccinated or not,” Bednarczyk said. The vaccine is less effective in those older than 26, but there are reasons that some may choose to get it and others may not.

For example, someone who is in their late 30s and has had more than 10 sexual partners—each of whom have had their own previous sexual partners—may decide that they have likely been exposed to multiple strains of HPV and that the vaccine may be less effective for them. Meanwhile, someone in their early 40s may have had only one or two sexual partners in their lifetime but is now going through a divorce and expects to become sexually active with more partners in the future, so they might consider HPV vaccination a good idea. Others may decide to get the HPV vaccine even if they are in a happy monogamous relationship in case something happens later, such as the unexpected death of a partner, or other life circumstances.

Who Shouldn’t Get the Vaccine

Some individuals are explicitly not recommended to get the HPV vaccine even if they fall within the recommended age groups. Anyone who has had a severe allergic reaction, such as anaphylaxis, to an ingredient in the HPV vaccine or to a previous dose of the HPV vaccine should not get any additional doses. One of the ingredients in Gardasil 9 is saccharomyces cerevisiae, or baker’s yeast, so people who have a history of hypersensitivity to yeast should not get the vaccine.

People who have a current infection, such as influenza or a more serious illness, can still receive the vaccine, but the CDC generally advises that people wait until the acute symptoms of the disease pass before getting the dose. If you have a fever, there is no evidence of a greater risk of side effects from the HPV vaccine, but getting the vaccine means you would not be able to tell if you develop a fever from the vaccine or if the fever is from the current infection. If your illness is minor, such as a cold, that’s not a reason to put off vaccination, according to the CDC.

People are not recommended to receive the HPV vaccine during pregnancy. If someone gets the vaccine and then finds out they are pregnant, however, they shouldn’t panic, because no studies have identified adverse events or increased risk of birth defects, miscarriage or stillbirth with HPV vaccination during pregnancy. In fact, a 2015 study looked at 147 women who received the vaccine while they didn’t know they were pregnant, and the study didn’t find any additional risks with vaccination.

Still, the vaccine has not been studied in a pregnant population during clinical trials, so there is not enough evidence for the CDC to recommend it during pregnancy. Instead, the CDC recommends waiting until after pregnancy to get the second or third doses.

The Pros of the HPV Vaccine

One major benefit of the HPV vaccine is prevention of genital warts, which affected an estimated 340,000 to 360,000 people every year before the vaccine became available. Even now, an estimated 1 out of 100 people at any given time has genital warts, according to the CDC. There is no medical treatment for an HPV infection, and most people don’t know when they have one unless they develop warts. Although prescription medication can treat the warts, they can return afterward. The only alternative to prescription medication for genital warts is cutting away the tissue.

By far the biggest benefit of the HPV vaccine is substantially reducing your risk of developing an HPV-related cancer, which accounts for 5% of all cancers worldwide. That may not sound big, but a small percentage of a big number is a lot of cancer—more than a half million women and 60,000 men each year. In the US, HPV is the cause of approximately 36,500 new cases of cancer every year, and the HPV vaccine prevents about 92% of those cancers. Cancers caused by HPV can take 10 to 30 years to develop, so you won’t know whether an HPV infection you contract—which likely won’t have any symptoms—could lead to cancer until decades later.

An estimated 14,100 cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed each year, and more than 4,200 women will die from the cancer in 2022. Yet nearly all cervical cancer is caused by HPV. The more women vaccinated against HPV there are, the more cases of cervical cancer will drop. Researchers estimated after the initial clinical trials that universal uptake of HPV vaccination could eliminate more than two thirds of cervical cancers worldwide—and that was before Gardasil 9 was available.

Cervical cancer cases have already been dropping in the U.S. since the 1950s due to routine cervical cancer screening with Pap smears, which allow physicians to identify abnormal tissue, such as precancerous cervical lesions. Cervical cancer cases in 2007 were four times lower than in the 1950s, thanks to these screenings. If these screenings are so successful, why would the HPV vaccine be necessary then?

“Cervical cancer is one of six cancers that are caused by HPV,” Bednarczyk said. “We don’t have screening tests for the other ones, so you’re still missing out on opportunities for prevention without vaccination.” In addition, cervical cancer screenings may not catch all cases, and some people may miss screenings. “Having as many opportunities for prevention as we can is really critical in terms of keeping people healthy,” Bednarczyk said.

Does It Really Prevent Cancer?

Some may also have questioned whether the vaccine really does prevent cancer because the clinical trials only looked for precancerous tissue to determine effectiveness. The study researchers chose to assess precancerous lesions because it can take so long—10 to 20 years—for cancer to develop, which would drag the clinical trials out for decades. However, a reduction in precancerous lesions is how researchers have measured how much Pap tests have reduced cervical cancer. “To argue that vaccine-induced prevention of [precancerous lesions] does not prevent cancer is akin to arguing that Pap smear testing does not prevent cancer,” wrote Bednarczyk, Kevin Ault and Daniella Figueroa-Downing in a peer-reviewed commentary.

In the last few years, however, enough time has passed since the vaccine’s introduction that researchers have been able to document a drop in cervical cancer deaths due to HPV vaccination. A study in JAMA from November 2021 showed a bigger decrease in cervical cancer cases and deaths among people ages 15 to 24 than among those ages 25 to 29 and 30 to 39. The difference in rates, also greater than decreasing historical trends and not correlated with changes in cervical cancer screening rates, strongly suggests the HPV vaccine is responsible for the drop more than any other potential reason.

Further, even if a cervical cancer screening detects precancerous lesions, the procedures to remove these lesions can be more painful and carry more side effects than HPV vaccination. Two examples of these treatments are a LEEP (loop electrosurgical excision procedure) and a cone biopsy, which is the removal of a cone-shaped piece of cervical tissue. A cone biopsy’s side effects include vaginal bleeding for about one week and spotting for up to three weeks. It’s also necessary to avoid intercourse and use of tampons for three weeks afterward. While a history of a cone biopsy does not affect a woman’s ability to get pregnant, it can slightly increase the risk of miscarriage or preterm birth, which the HPV vaccine does not do.

Patricia, a 31-year-old from Dallas, said the doctor recommended the vaccine for her when she was 12 years old, but her mother turned it down. ”She was [a] very close-minded Catholic at the time and thought I was too young to be talking about sexual stuff,” Patricia said. ”Now I, unfortunately, have HPV and continuously have to get colposcopies. I wish she had gotten me the shot to at least give me a better chance of not getting it.” A colposcopy involves a doctor widening the vagina to examine the cervix for any abnormal tissue and, if necessary, taking a tissue sample (biopsy) of any suspicious tissue.

“Honestly, the more I have to get, the more they hurt. The last time my blood pressure dropped from the pain,” Patricia said. The emotional distress of waiting for the results to find out if she has cancer is also nerve-wracking, she added. ”I know once my daughters are of age, I will not refuse it.”

Prevention of Other Cancers

While cervical cancer is the biggest HPV-related threat to females, the biggest threat to males is oropharyngeal cancer, or cancer of the mouth and throat. Oral cancer, like the other cancers caused by HPV, do not have routine screenings that can catch the cancer before it grows. The biggest risk factors for oral cancer are HPV infection and smoking, but even as smoking rates have declined, oral cancer rates in men have steeply increased. An estimated 1 in 60 men and 1 in 140 women will develop oral cancer in their lifetime, and oropharyngeal cancers caused by HPV in particular have been rising. According to a study in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery in December 2021, it’s not only the number of cases of oral cancer that are increasing—it’s also deaths. Mortality from oropharyngeal cancer increased 2.1% per year among men, the researchers found.

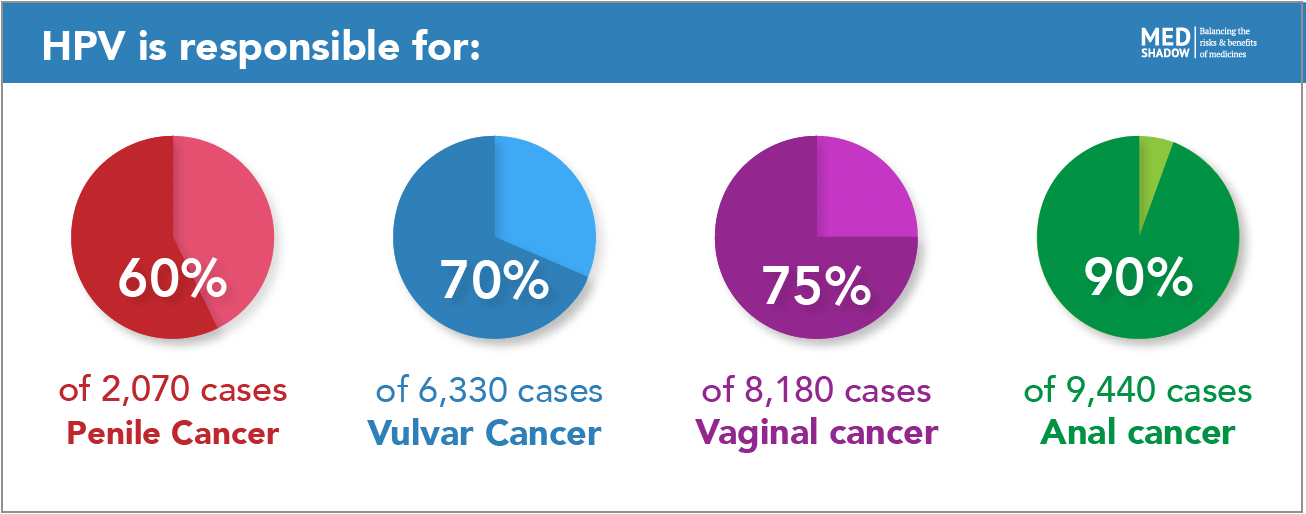

The other four cancers that HPV can cause occur less frequently than cervical and oral cancer, but they can be just as deadly. HPV is responsible for:

- 90% of the 9,440 cases of anal cancer and 1,670 deaths each year

- 75% of the 8,180 cases of vaginal cancer and 1,530 deaths each year

- 70% of the 6,330 cases of vulvar cancer and 1,560 deaths each year

- 60% of the 2,070 US cases of penile cancer and 470 deaths each year

Cons of the HPV Vaccine

While the HPV vaccine’s benefits include preventing multiple types of cancer, all medications and vaccines have side effects, and the HPV vaccine is no exception. Compared to other vaccines, however, Gardasil actually has fewer side effects than most vaccines. Information about the side effects of the HPV vaccine come from both before and after the FDA approved it for use. Before FDA approval for females and later males, the first Gardasil vaccine was studied in more than 29,000 males and females during clinical trials. Then, Gardasil 9 was further studied during clinical trials in more than 15,000 participants.

The most common side effects of the HPV vaccine are common to other vaccines as well:

- Pain, redness, or swelling in the arm where the shot was given occurred in 20% to -90% of people who received the vaccine during clinical trials

- A fever up to 100ºF occurs in 10% to 13% of people during the two weeks after receiving the vaccine, but a similar proportion of people in the placebo group experienced a fever

- Nausea

- Headache or feeling tired

- Muscle or joint pain

- Dizziness or fainting

Nausea, headache, fatigue, muscle pain, and joint pain also occurred in the placebo groups during the clinical trials at about the same frequency as in the vaccine groups. However, dizziness and fainting was more common in the vaccine group and can potentially be the most dangerous. It’s also more common among teens than older adults and is a possible side effect of any vaccine given to teens. According to Bednarczyk, fainting is a good example of a side effect discovered after the clinical trials due to continued CDC and FDA monitoring of the vaccine’s safety. After multiple reports of fainting to Vaccine Adverse Event Monitoring System (VAERS), researchers investigated and discovered that fainting was associated with the HPV vaccine. “Then we changed the recommendations to make sure this wasn’t going to cause any secondary problems,” Bednarczyk said. “This was the system working exactly like it should to find and respond to issues that may arise.”

The danger with fainting is potential injury from the fall itself, including concussion. ”There have been some young adults and children who have gotten their vaccine and jumped up, trying to run out the office, and fainted and hit their head on the edge of the exam table,” Ault said. The CDC now recommends that adolescents be sitting down or lying when they get the vaccine and then remain sitting or lying down for 15 minutes afterward.

Even when someone does remain sitting or laying down, these temporary reactions can be frightening, as Kell, a mother in Florida, described. “We have a family member currently dying of HPV-related throat cancer, so it’s an important vaccine for our family, specifically,” said Kell, who preferred not to share her last name. But when her 11-year-old daughter received her first dose of Gardasil, she experienced her first-ever vaccine reaction. “Within seconds of the HPV shot, she started jerking around and passed out off the table. She was clammy and sweating and gray when she came,” Kell said. “She’s fine now, but it was certainly a scare for me and her little brother.” But Kell’s daughter will still get the second dose when it’s time. “We’ll absolutely continue the series because, even if it makes you pass out, it’s still better than cancer, but I will insist the next one be given while she’s laying on the table.”

The rarest type of side effect is a severe allergic reaction, such as anaphylaxis, which can occur in approximately 1 out of 1 million individuals, about the same risk of severe allergic reactions to other vaccines, Ault said. “At most facilities, injectable drugs like vaccines are going to have a protocol in place for that rare reaction,” he said, and it’s the reason healthcare providers usually ask people to wait 15 minutes after a vaccination before leaving.

Although pain is a possible side effect from any vaccine, the HPV vaccine is known for being more painful than other vaccines. In addition, a 2012 study found that there may be an increased risk of skin infections at the injection site after Gardasil vaccination compared to not receiving the vaccine. The reason it’s more painful than other vaccines is that a key component of the vaccine is the “big chunk of protein” that looks like the outer shell of the virus and stimulates the immune system to produce antibodies against it, Bednarczyk explains. To keep that protein stable in the solution requires a lot of salt, which can make the localized reaction to the vaccine stronger.

That doesn’t mean it’s painful for everyone though. Juniper Russo, from Chattanooga, Tennessee, said it was painless for her daughter, who didn’t experience any side effects of the HPV vaccine at all. “Her grandmother, my mother, nearly died of advanced cervical cancer in the 1990s, and I’m very glad to know my daughter won’t suffer the same,” Russo said.

What About Long-Term Side Effects of the HPV Vaccine?

If it seems like this is a short list of side effects, then you may have seen other claims online about more serious conditions caused by the HPV. Unfortunately, more misinformation exists about the HPV vaccine than most other vaccines, causing greater fear and anxiety among parents and those considering getting the vaccine.

One source of this confusion is a misunderstanding of the term adverse event. An adverse event is any negative health incident that happens after receiving a vaccine—whether it’s related to the vaccine or not. For example, if someone got into a car accident or fell and sprained their ankle after getting a vaccine, this would be considered an adverse event even though no one would say that the vaccine caused those events. A side effect, on the other hand, is an adverse event that is known to be caused by the vaccine.

All adverse events that occur during vaccine clinical trials are listed on the product information insert of the vaccine. However, this list includes all things that occurred in both the group that received the vaccine and the group that received the placebo—regardless of whether the adverse event was actually a result of getting the vaccine. Similarly, people who receive the vaccine after it’s approved can—and should—report any adverse events they experience to the Vaccine Adverse Event Monitoring System (VAERS). VAERS is a passive surveillance database, which means it collects information that others enter without regard to whether the incidents reported are related to the vaccine in any way other than occurring after it was administered.

People frequently misinterpret the adverse events listed in vaccine inserts or in VAERS to mean that those adverse events were all caused *by* the vaccine, but that’s not how the system works. The only way to determine whether a vaccine actually caused an adverse event—and that it’s therefore a possible side effect of HPV vaccination—is to compare how often that adverse event occurs in people who received the vaccine and those who didn’t. Or, another type of study compares how often the adverse event occurred in the weeks or months after getting the vaccine to how often it occurred in the same population before they received the vaccine. In either case, researchers can statistically calculate whether the vaccine itself was the cause or whether the adverse events occurred after the vaccine coincidentally.

Researchers have conducted these studies on the HPV for a wide range of conditions to determine whether the vaccine can cause any serious health conditions, such as infertility, an autoimmune disease or another condition. Sometimes studies have identified more diagnoses of a condition occurring among those who receive the HPV vaccination—but not because the vaccine caused the condition.

“The simple act of going to the doctor and getting the vaccine may lead to a situation where the doctor discovers a condition that already was there,” Bednarczyk explained, especially if the person hasn’t seen their doctor in a while. For example, if a teen gets the vaccine during a well visit and the doctor decides to do a complete workup with bloodwork, the bloodwork might later reveal a condition like diabetes, which will appear on their medical chart as occurring immediately after vaccination. “There’s no way that vaccine could have triggered it, because the blood draw was taken on the same day that the vaccine was given,” Bednarczyk said. Scientists therefore design their studies very carefully to account for these possibilities and avoid false safety signals.

So far, researchers have not identified any serious or long-term health conditions caused by the vaccine. Below is a list of conditions that scientists have investigated and found to be unrelated to the HPV vaccine:

- Risk of Guillain–Barré Syndrome (GBS), stroke, blood clots, appendicitis, or seizures is no different after HPV vaccination than without vaccination, according to a 2011 study.

- Another study in 2012 also investigated the risk of blood clots as well as autoimmune disease and found no link between either of these and HPV vaccination, and a 2014 study confirmed no link with blood clots.

- Two studies, one in 2012 and one in 2014, examined autoimmune diseases and found they were no more likely after HPV vaccination than in those who didn’t receive the vaccine, and a review of all major studies on this topic in 2018 similarly found no connection.

- A study in 2020 investigated multiple autonomic dysfunction conditions, including postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), chronic fatigue syndrome and complex regional pain syndrome and found no evidence that any of these conditions were caused by HPV vaccination.

Infertility Worries

Most of the concerns related to infertility after the vaccine have come from scattered reports of girls experiencing ovarian failure or primary ovarian insufficiency, when the ovaries don’t function properly. Ovarian insufficiency affects about 1 in 10,000 females independent of vaccination.

“When you’re preventing infection with a virus that, by and large, affects the reproductive tract, it leads to concerns about what the vaccine can do in that part of the body, but vaccines don’t work that way. They work on our immune system,” Bednarczyk said.

After a couple case studies were published about ovarian insufficiency after vaccination, researchers investigated it more closely with larger populations. In the largest of these studies, a 2018 study in Pediatrics with nearly 200,000 participants, the researchers found no increased risk after HPV vaccination or vaccination with two other adolescent vaccines, the meningitis and Tdap vaccines.

One reason people may have attributed ovarian insufficiency to HPV vaccination is related to birth control pills, Bednarczyk and Ault explained. It’s common to prescribe teenagers birth control pills if they have an irregular menstrual cycle, Ault said, and they continue taking the birth control when they become sexually active. But oral contraceptives can disguise irregular cycles that continue beyond adolescence into a woman’s 20s and 30s, and one cause of irregular cycles is ovaries not releasing eggs on a regular basis. But a woman may not know she has irregular cycles until she stops taking birth control. ”Anything that may have been happening in the background, separate from vaccines, may have been masked,” Bednarczyk said.

Some of those who originally published case studies on ovarian insufficiency also published papers claiming that the HPV vaccine caused a new condition they called ”autoimmune syndrome induced by adjuvants,” or ASIA. After additional reports about ASIA with inconclusive evidence, researchers conducted a review of the research on ASIA and found no evidence that this syndrome exists or that its symptoms were linked to the HPV vaccine or any other vaccines.

Finally, a common concern among parents especially soon after the HPV vaccine’s approval was that vaccinating kids against a sexually transmitted infection might send the message that teens can begin having sex. Multiple studies have looked at whether teens who get vaccinated are any more likely to start having sex sooner than unvaccinated teens. Scientists found again and again that HPV vaccination did not encourage sexual activity or increase the likelihood that vaccinated teens would begin having sex sooner than any of their unvaccinated peers. In fact, to make sure the researchers did not need to rely only on teens’ answers about their sexual activity—which may not be truthful—studies looked at rates of other sexually transmitted infections and pregnancy rates among teens who did and did not receive the vaccine.

“We found no differences between the HPV-vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in terms of those risks,” Bednarczyk said. He said the concern about increased early sexual activity may result from parents’ anxiety related to thinking about their children eventually having sex at all. “Parents don’t want to think about their adolescent kids being sexually active just in general, and to give a vaccine like HPV vaccine is an acknowledgment that my child is at some point in time going to be a sexual person,” he said. But that’s also why it’s so important to give the vaccine early, before there’s any real possibility of teen sexual activity. ”Just as we do not wait until we have been in the sun for two hours to apply sunscreen, we should not wait until after an individual is sexually active to attempt to prevent HPV infection,” he wrote in an article about addressing parents’ concerns.

It’s also important to note that, unlike some other sexually transmitted infections, HPV can be transmitted among partners of any gender, Ault said, and transmission does not require intercourse.” You can get HPV from female partners, you can get it from male partners, males can infect other males and women can affect other women, so it’s kind of a unique situation in that regard,” Ault said.

8 Questions to Ask Your Child’s Pediatrician About the HPV Vaccine

- Do you recommend the HPV vaccine?

- What kind of side effects have you seen immediately after the shot?

- Based on how the vaccine works, do you think there will be long-term adverse effects?

- How long have you been giving this vaccine?

- Do you know of any serious adverse events among your patients or in this area?

- Would you give this vaccine to your child?

- If I get this vaccine for my child, what reactions should I be on the alert for?

- What kinds of reactions or symptoms should lead me to call you or seek medical attention if my child experiences them?

- How long will protection from the HPV vaccine last?