[Editor’s note January 2023: Evusheld is no longer authorized for COVID-19 prevention, since it does not appear to be effective against the newest variants.]

None of the COVID-19 vaccinations guarantee immunocompromised people much protection from the disease, but now the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an antibody engineered to protect you from getting COVID-19.

Only 27% of transplant recipients, for example, who are severely immunocompromised, mounted a sufficient antibody response after two doses of an mRNA vaccine, made by Moderna and Pfizer. The immunocompromised state is due to drugs prescribed to prevent their immune systems from rejecting a new organ.

The FDA lists the following conditions as likely to leave you moderately or severely immunocompromised:

- Active treatment for solid tumor and hematologic malignancies

- Receipt of solid-organ transplant and taking immunosuppressive therapy

- Receipt of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T-cell or hematopoietic stem cell transplant (within 2 years of transplantation or taking immunosuppression therapy)

- Moderate or severe primary immunodeficiency (e.g., DiGeorge syndrome, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome)

- Advanced or untreated HIV infection (people with HIV and CD4 cell counts <200/mm3 , history of an AIDS-defining illness without immune reconstitution, or clinical manifestations of symptomatic HIV)

- Active treatment with high-dose corticosteroids (i.e., ≥20 mg prednisone or equivalent per day when administered for ≥2 weeks), alkylating agents, antimetabolites, transplant-related immunosuppressive drugs, cancer chemotherapeutic agents classified as severely immunosuppressive, tumor-necrosis (TNF) blockers, and other biologic agents that are immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory (e.g., B-cell depleting agents)

If you are not vaccinated, it can take time for your immune system to develop antibodies to fight off an infection. Unfortunately, the virus can wreak havoc during that time. One of the earliest treatments for people infected with COVID-19 was monoclonal antibodies, which were created in a lab and injected directly into patients to neutralize the virus before it could cause severe disease. For much of the pandemic, these treatments have helped save lives. But while a vaccine teaches your body to make its own antibodies to protect against future infections, an infusion of synthetic antibodies quickly disappears within days or weeks without teaching your immune system this lesson.

In the lab of James E. Crowe Jr. at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, scientists developed two antibodies, engineered to last longer than the antibodies designed for treatment. The center has licensed them to AstraZeneca to make Evusheld (tixagevimab and cilgavimab), a drug that can provide protection from COVID-19 in immunocompromised patients who don’t mount a response to the vaccine, and for those with severe reactions who can’t be vaccinated.

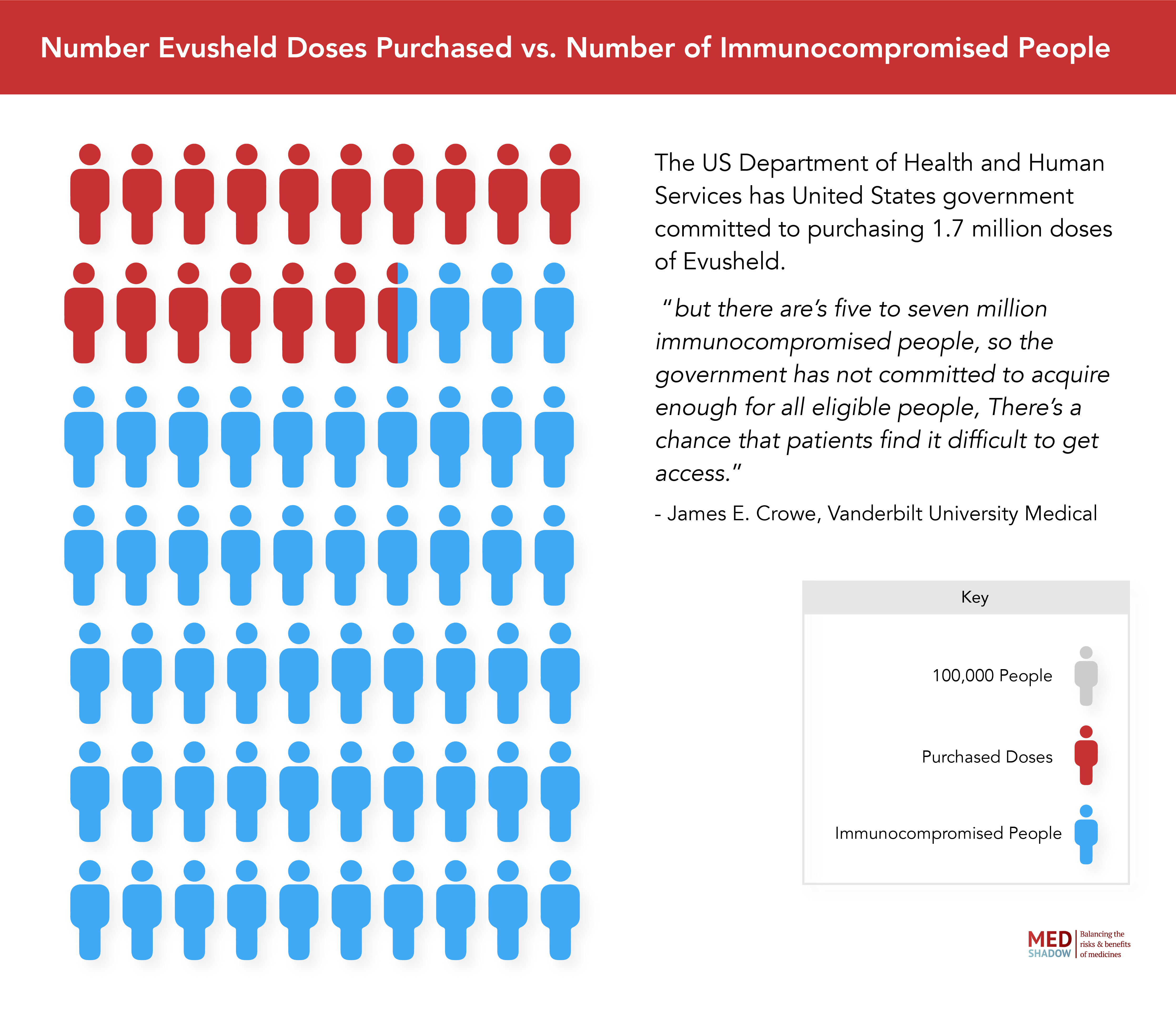

The US Department of Health and Human Services has committed to purchasing 1.7 million doses of the drug in February 2022, “but there are five to seven million immunocompromised people, so the government has not committed to acquire enough for all eligible people,” says Crowe. “There’s a chance that patients find it difficult to get access.”

However, The New York Times reports that challenges in getting access are more likely to stem from confusion among both patients and doctors about when to use it, than it is about being unavailable.

For example, Susanna Speier, author of the Immunocompromised Times newsletter takes an immunosuppressant drug, Remicade, to treat her Crohn’s disease. Her doctor told her that Evusheld wasn’t for her. According to the CDC’s list, she may be immunocompromised, but she’s not immunocompromised enough. She did qualify for the vaccine, and got her three shots, but was still concerned about her waning immunity. Even if her body did build a response to the shots, would it fade faster than others? Would it be weaker than someone who isn’t immunocompromised?

She heard about the extra protection that Evusheld might provide to someone like her. When her doctor wouldn’t facilitate an appointment for her, she turned to support groups for immunocompromised people and managed to find an appointment nearby. “I was trying to be a hacker for my own health,” she says.

Finding the appointment was a challenge, but actually getting the shots was easy. “The shots themselves felt like twin bee stings, one in each buttock, at point of injection, but once the needles were removed the pain also went away. No lingering sorenesses,” she says.

After getting Evusheld, Speier was the “most social she’s been” since the pandemic started. She took precautions like testing herself and sitting outside at restaurants, but she was thrilled to travel and visit friends and attend her mother’s outdoor wedding. Now, however, her antibody levels have dropped to half of what they were after she received Evusheld. It’s not clear how many antibodies are required for adequate protection, but she’s scheduling her next dose and hopes it’ll help keep her safe during the winter months.

Unfortunately, during the start of the Omicron surge, scientists found that several of the antibodies they were using to treat patients already infected were no longer able to neutralize the new variant. That wasn’t true using Evusheld, which still maintained much1 of its efficacy. However, newer Omicron subvariants are gaining ground, that at one variant, BA4.6 , which makes up at least 14% of COVID-19 cases, seems able to evade Evusheld antibodies. Several companies, including the manufacturer of Evusheld are racing to develop new long-acting antibodies to protect the immunocompromised, though experts warn it may be months or even a year before they are ready.

In March of 2022, MedShadow spoke with Crowe about who can use the drug and what you need to know about it.

Editor’s note: This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

MedShadow: What is Evusheld? How is it different from other antibodies used to treat people who are already infected with COVID-19?

Crowe: There are two main differences between Evusheld and the others. One is that the antibody has been engineered to be long-acting. So it has a half-life of about three months instead of three weeks. The benefit of that is that it can be used for prevention, rather than just treatment.

The other is that the antibodies were modified in a way that reduces their interaction with the body’s immune system. They were engineered so they just interact with the virus and they don’t interact with the body’s immune system. That was done for safety, because we didn’t think we could control what the antibodies were doing, so it doesn’t contribute to inflammation. It simply deals with the virus.

MedShadow: How should it be taken? Do patients need multiple doses?

Crowe: There are two antibodies [in Evusheld], and they were put in separate vials. So when Evusheld is administered, you actually get two shots.

Now Omicron is a much different virus than all the variants before. Many of the antibodies [used for treatment] completely lost activity [against Omicron]. Evusheld still has significant activity, but it has reduced activity. The company and the FDA did very sophisticated calculations and they concluded that using twice as much antibody is desirable, if you can do that, with Omicron. So the FDA issued an advisory that you would actually get twice as much of each of the antibodies. As a consequence, if patients had only gotten the normal dose, [the FDA] advised that they get another dose of it.

MedShadow: Who could benefit from receiving injections of Evusheld?

Crowe: It’s for basically people who cannot be immunized with current vaccines. So these are people who are moderately to severely immunocompromised, due to some medical condition, or else because they have been given immunosuppressive medicines or treatments. They can’t respond well to vaccination.

Or there are rare people who have had severe adverse reactions like an allergic reaction to a COVID-19 vaccine, or components of a COVID vaccine, and those people are eligible to get it.

You’re not supposed to get it if you have COVID. You’re not supposed to get it if you’ve been exposed to COVID-19 , which is called postexposure prophylaxis. It’s currently only approved for prevention. And you have to be over 12.

There are considered to be five to seven million immune compromised people in the US, which is quite a large number of people.

MedShadow: What kinds of side effects should patients know about?

Crowe: In the trials, the most common side effects have been mild things like headache and fatigue and sometimes cough. Those were the things that were noted. Whether or not they’re due to the antibody is not all that clear.

Sometimes patients will have an allergic reaction. It’s very rare, and that’s not about Evusheld specifically. That’s for all antibodies that may give you an allergic reaction.

Any time you give a shot in the muscle, if you have a bleeding disorder, you have to be careful with that because you’re using a needle [which can lead to intramuscular bleeds].

A lot of the people in the trials were high-risk individuals, and there were cardiac events in people during the trials. And some of the people who got Evusheld had cardiac events like heart attacks. But it’s not clear that the drug caused those. If you are really [at] high risk for heart attacks, you have to think about an uncertain risk, [whether you] would do it or not? Personally, I would do it. I’d rather have the drug and prevent COVID-19 . [Editor’s note: in the clinical trials, 0.6% of patients who received the antibodies had a cardiac event compared to 0.2% of patients who received a placebo. One person who received the drug died.]

MedShadow: How effective is Evusheld against Omicron?

Crowe: Trials have not been done specifically with Omicron, so I can’t really say what would happen clinically. But we have the new viruses and we have the antibodies. We mix them in the lab and then measure the concentration needed to inhibit the virus. And if you need more concentration for Omicron, than you did for Delta, then you say the “activity is reduced.” At the doses we’re giving, even at the reduced potency, it’s expected that it would work.

There have been some misunderstandings about the in vitro findings. We expect the drug to still work, but more studies are being done. [Those studies are asking] how well does it work and how long does it work? But it’s predicted to benefit patients.

The important information for patients and providers is that the prophylaxis should still be a benefit and be used.