About one in eight people in the U.S. will develop some sort of thyroid condition during their lifetimes, according to the American Thyroid Association, so there’s an excellent chance you or someone you know is taking levothyroxine (brand name Synthroid), a thyroid-replacement medication. In fact, levothyroxine is one of the most commonly prescribed drugs in the United States right now, as it has been for much of the past decade.

It’s especially helpful, then, to know what other drugs can interact with levothyroxine or what other drugs can otherwise affect thyroid function, potentially causing someone to begin taking the drug. The New England Journal of Medicine published such a comprehensive review of these interactions and side effects that it may be worth printing out and hanging on to if you need to have a conversation with your doctor about your or a family member’s thyroid.

“Medications that might interact with your thyroid medication may cause your thyroid medication to not work properly, leading to ineffective treatment of your thyroid disease,” explained Deena Adimoolam, MD, an assistant professor of endocrinology, diabetes and bone disease at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

Or, people with no existing thyroid problems may develop a condition, such as certain cancers, whose treatments can begin messing with the thyroid. In either case, knowing the possible side effects of drugs you’re taking and talking to your providers about them can ensure one of your body’s most important hormones keeps flowing.

How Your Thyroid Works—Or Doesn’t

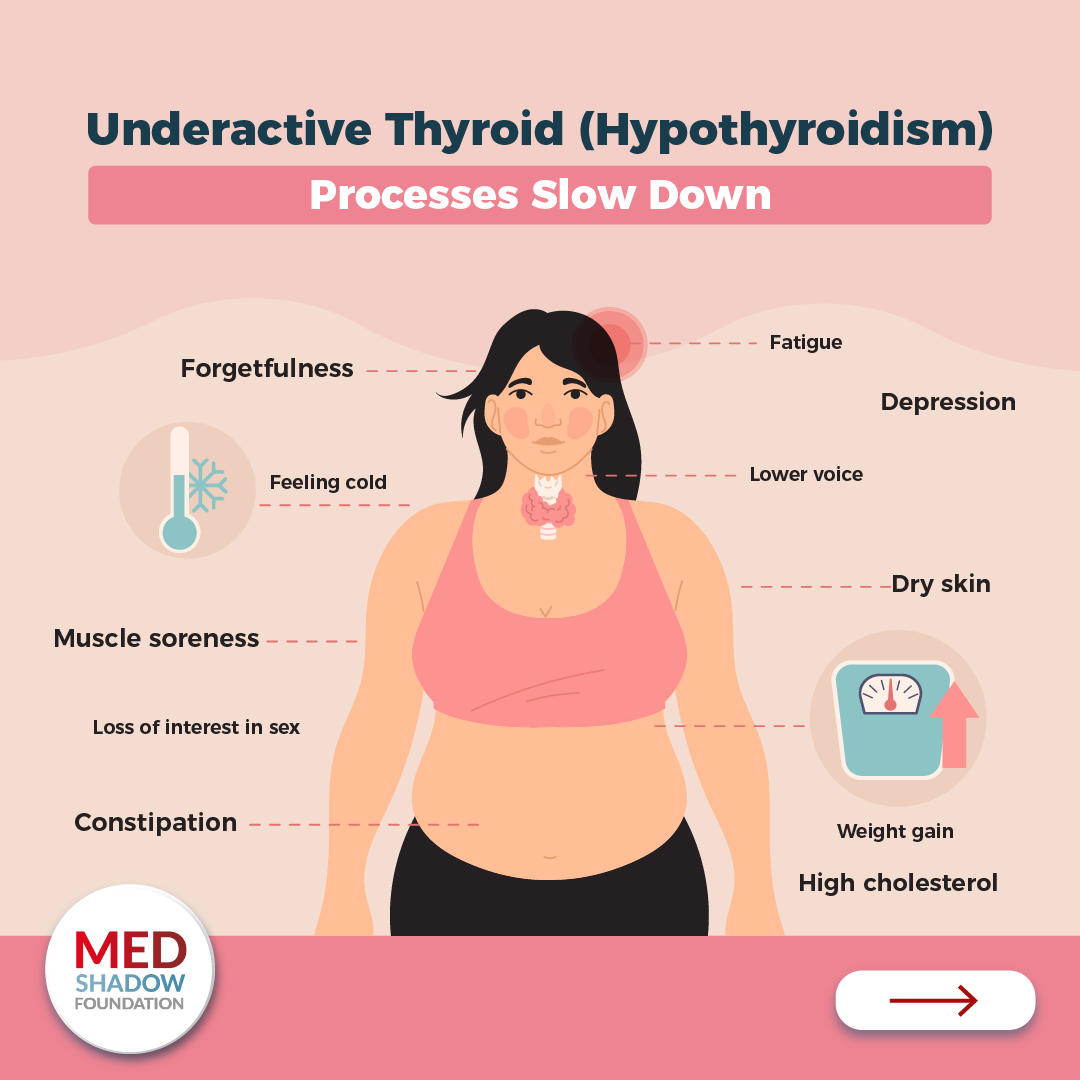

The thyroid gland, located in your neck, produces hormones that regulate metabolism, digestion, heart function, muscle control, brain development, bone health and even mood. Dysfunction in the thyroid, then, can lead to a wide range of symptoms.

Hypothyroidism, where the gland does not produce enough hormone, can cause fatigue, though feeling tired is often so common and general that it’s not a good indicator on its own of thyroid dysfunction, explained Kathryn G. Schuff, MD, a professor of endocrinology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

“Other symptoms of hypothyroidism, or low levels, include feeling cold when everybody else around you is okay, a little bit of constipation, potentially a little bit of swelling and puffiness and a little bit of weight gain,” Schuff said.

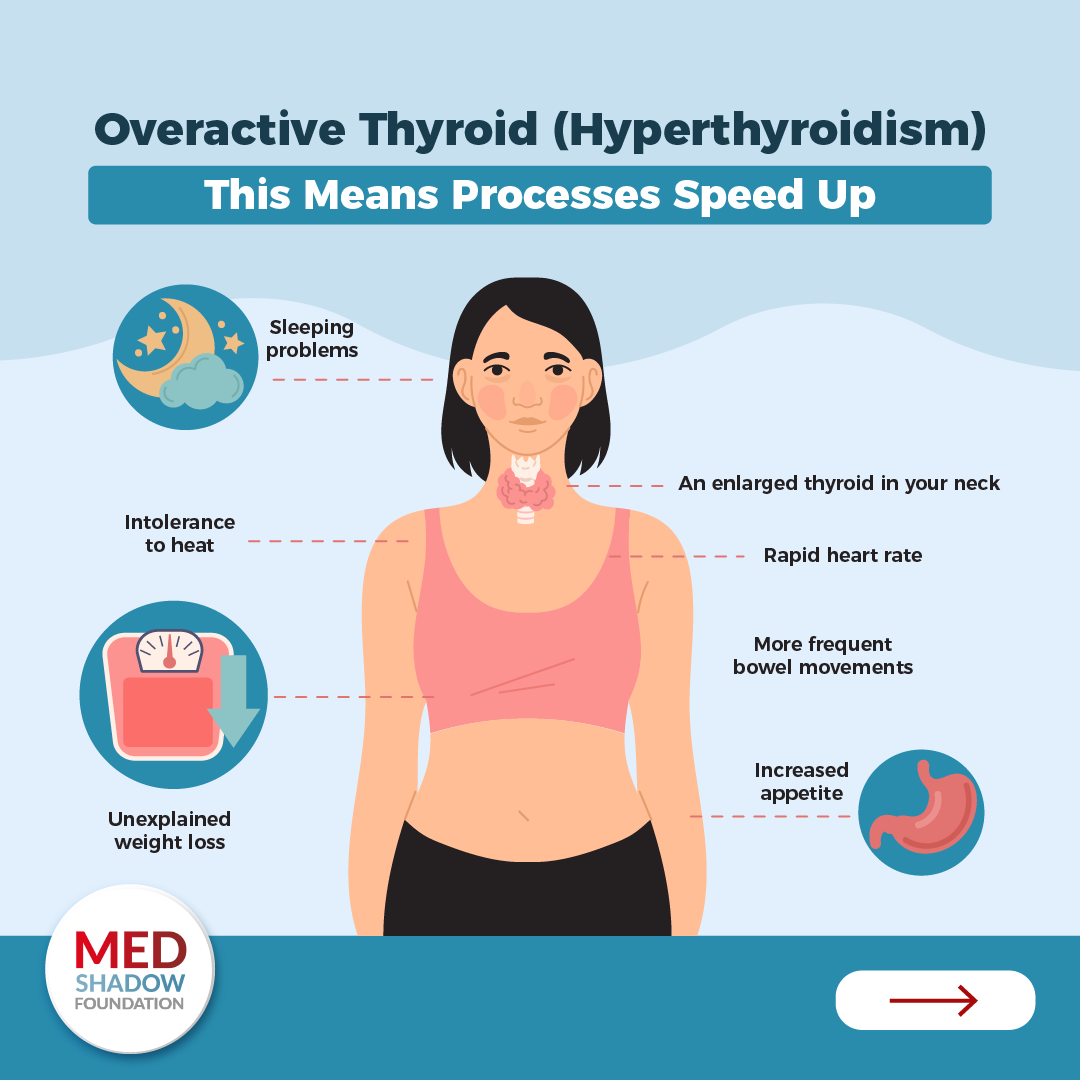

Hyperthyroidism, on the other hand, where hormone levels are too high, can cause a racing heart rate, difficulty falling asleep, anxiety and sometimes tremors.

“People who have hyperthyroidism will notice heart palpitations, feeling very warm and sweaty and losing weight unexpectedly,” said Anne Cappola, MD, ScM, a professor of medicine in the division of endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism at the University of Pennsylvania. But she adds that many people might have these symptoms even with a normal thyroid, so it’s only if they experience a clear, sudden change that they should talk to their doctor about testing their thyroid.

Those who have low thyroid levels take levothyroxine to replace what their body isn’t getting. It’s easy to adjust the dose of levothyroxine, the endocrinologists explained, but it’s important to know when it’s needed, and what drug interactions might require adjustment.

3 Ways Drug Side Effects Can Affect Your Thyroid

There are three main ways a medication can interfere with your thyroid or with levothyroxine, described Henry B. Burch, MD, of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, in the new NEJM article.

Drugs Can Disrupt Natural Thyroid Hormone Function

The first is by interfering with your body’s natural thyroid function. There are many ways a drug might do this. Understanding the details of all these processes is not as important as understanding that many ways exist for a drug to hinder your body’s ability to get and use thyroid hormone the way it should. However, some ways a drug could interfere with your thyroid function are by changing the amount of hormone released, changing the amount of thyroid hormone produced, enhancing thyroid autoimmunity, causing changes in the proteins that the hormone binds to in the body, preventing the hormone from binding to those proteins, interrupting the body’s ability to convert the hormone into different forms (such as T4 to T3) or increasing thyroid hormone metabolism.

Drugs Can Interfere with Thyroid Hormone Therapy

The second way is for a drug to interfere with thyroid hormone therapy, primarily levothyroxine. Another medication could decrease the absorption of levothyroxine, affect how well the pill itself dissolves, decrease the thyroid hormone levels in the body or increase the metabolism of it.

Drugs Can Interfere with Thyroid Hormone Labs

Finally, some drugs or supplements do not actually affect your thyroid function—but they appear to on lab tests. Biotin, or vitamin D7, for example, can interfere with blood testing of thyroid levels and give false readings.

“It has nothing to do with someone’s thyroid function or the dosing requirements, but it can affect the test results and make someone’s thyroid look over-active or under-active,” Cappola said. “The concern is that someone may act on that,” making unnecessary or inappropriate dosing adjustments. She advises those who take biotin supplements to stop taking them three days before any blood tests to check thyroid levels.

Common Drugs That Can Mess with Your Thyroid

The vast majority of the time, interactions from taking other drugs along with a thyroid medication do not cause toxic effects but instead can cause fluctuations in a person’s thyroid levels that may then need adjustment, Schuff said.

“Even though this list is hugely long, the vast majority of these interactions are very minor and mild and really don’t cause the person any problems,” Schuff said about the medications listed in the NEJM review.

That means it’s particularly important for patients to be sure their physicians, both primary care doctors and any specialists they see, know all the medications they’re taking.

“Many, many drugs can cause changes in how the thyroid hormone is absorbed, how it is metabolized or how the thyroid hormone circulates in the blood can bind with the proteins,” Schuff said. “All of those can result in a need to change the dose the person is on.”

How PPIs May Impact Your Thyroid

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), available over-the-counter and by prescription, are a common example of a drug group that can interact with levothyroxine. These drugs are recognizable because their generic names always end in “–prazole.” They include:

- Lansoprazole (Prevacid)

- Omeprazole (Prilosec)

- Esomeprazole (Nexium)

- Dexlansoprazole (Dexilant)

- Omeprazole (Zegerid)

- Pantoprazole (Protonix)

- Rabeprazole (Aciphex).

Since PPIs reduce stomach acid, they’re very effective for treating acid reflux, heartburn, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and stomach ulcers. But reducing the acid in the digestive system can affect the absorption of other drugs, including levothyroxine.

“Any time that someone gets a new medication the doctor should be reviewing their medications to see if there’s going to be an interaction,” said Cappola, but that’s also true if you start taking a new drug over-the-counter.

Birth Control and HRT Can Affect Your Thyroid

People taking any drugs containing estrogen, including oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy, should also be aware of possible interactions with levothyroxine. Estrogen is one of those substances that can affect how the thyroid hormone binds to proteins in the body. This possibility includes non-prescription treatments for menopause symptoms that contain natural estrogen, such as compounded bioidentical formulas, Cappola said. She said that menopausal women often experience fluctuations in their body’s natural estrogen levels that then require changes in levothyroxine dosing.

Over-the-Counter Drugs and Supplements and Your Thyroid

People taking levothyroxine are advised to take it on an empty stomach because food can reduce its absorption, but some drugs can affect absorption too. This includes “seemingly innocuous over-the-counter drugs” and supplements, Cappola said, such as iron and calcium. The solution, she said is “to separate those medications that interfere with absorption by at least four hours” from when you take your levothyroxine.

Women who are pregnant or trying to conceive and taking a prenatal vitamin should also separate the vitamin from their levothyroxine by at least four hours.

And be wary of supplements marketed specifically to help your thyroid.

“Supplements for ‘thyroid health’ or ‘iodine supplement’ or ‘sea kelp supplements’ should be avoided as they are not always FDA-approved, and excess iodine can interfere with thyroid function,” Adimoolam said.

Many Other Medicines Affect Your Thyroid

A wide range of less common drugs, or drugs for very specific conditions, can also have interactions with levothyroxine or side effects that affect the thyroid in people without an existing thyroid condition.

These drugs include:

- Antiarrhythmics (such as amiodarone for atrial fibrillation)

- Glucocorticoids

- Antiepileptics

- Checkpoint inhibitors

- Lithium for mental illness

- Cancer immunotherapy drugs such as nivolumab and sunitinib

- Mitotane for adrenocortical carcinoma or

- Bexarotene for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, a type of skin cancer

A specialist who prescribes drugs like those above, is likely to be aware of its impact on your thyroid, but it never hurts to ask. “The cancer doctors are very, very savvy about these and know to monitor for changes in thyroid function,” Schuff said. A cardiologist prescribing amiodarone, for example, will monitor patients with thyroid testing every few months to ensure their levels are appropriate, or to adjust them as needed.

“The goal when you’re taking something is to catch it before someone becomes symptomatic,” Cappola said, but she cautioned patients not to feel overwhelmed. “Unless you’re an expert in this, there’s no way you can keep track of all the medications,” she said. Instead, keep an open line of communication with all your providers. “Certainly it’s worth asking, any time you start a medication, ’Can this affect any of my other medications?’” she said.

Some drugs, particularly those used to treat certain cancers, may be too new for researchers to have determined the best surveillance protocol—how often to test for thyroid changes—but patients can inform their doctors of changes they experiences, such as symptoms of hypo- or hyperthyroidism, and adjusting hormone levels is straightforward.

“We have really precise dosing, in 12 mg increments, so even minor changes can affect the dose requirements, and people can notice very subtle changes,” Cappola said. “So we like to stay on top of that and make sure the replacement is right.”

Am I Going to Develop a Drug-Induced Thyroid Problem?

Some individuals may be at higher risk for developing a thyroid condition as a result of medication even if they have not previously had any problems with their thyroid. Knowing your risk is higher can help you stay vigilant about your health.

These people include people with:

- Autoimmune issues, such as celiac disease, Hashimoto’s, type 1 diabetes, vitiligo

- Family history of autoimmune disease

- Thyroid nodules or other structural abnormalities

If you experience symptoms of hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, let your doctor know, but more importantly, keep an open line of communication with all your healthcare providers about all the drugs—prescribed, over-the-counter and supplements—you take.

“The biggest take-home point,” Schuff said, “is if you’re on levothyroxine and someone starts you or stops you on a medication, let the person who prescribes your thyroid medicine know.”