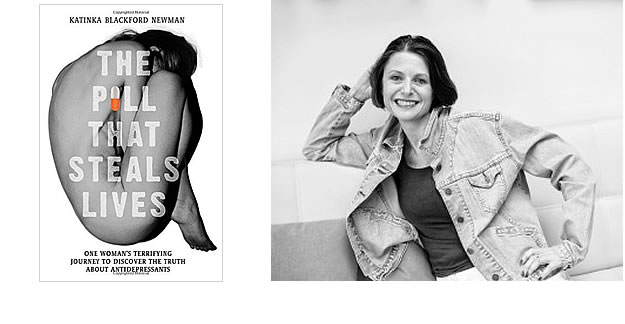

The following is an excerpt from Katinka Blackford Newman’s book, The Pill That Steals Lives, which will released on September 15. My ex-husband Robert and I have been separated for 8 months and we’re barely on speaking terms. All night I’ve been lying awake with terrible heart palpitations, an unnamed anxiety, a feeling of inexorable doom and need for antidepressants. I’ve been feeling strange for two days now, ever since I went to see a psychiatrist near Harley Street.

I visited him in desperation after I hit a wall of gloom on realising we had to sell our family home in northwest London. It was one of the few moments in my life when I had felt totally out of control.

The elderly man in the booklined office off Euston Square had looked at me sternly and asked if I had been crying a lot. The answer was undoubtedly “yes”. He asked me how I’d been sleeping and whether I’d stopped enjoying things I used to enjoy. Our 20-minute interview ended with him pronouncing that I was depressed. He wrote out a prescription for an antidepressant drug I’d never heard of called escitalopram, and another called mirtazapine, and told me to come back in a week. I wasn’t sure if I agreed with his diagnosis but now I’d spent a few hundred pounds on my appointment and he seemed to know what he was talking about. While I hadn’t heard of escitalopram, I’d heard of its cousin — Prozac.

It was a matter of hours after first taking the escitalopram pill that I started behaving oddly. I became very withdrawn and was unable to sit still. I now know that I was suffering one of the well-known side-effects of antidepressant poisoning called “akathisia” — where quite literally you are so anxious, you have to continually walk around. Soon after I felt I had lost the power of speech. It was as if something else was taking over my mind and body. The children, Oscar, 10, and Lily, 11, knew something was wrong and they phoned Robert, my ex, to tell him Mummy was behaving oddly, would he please come round. I was pacing up and down, crying, unable to talk or engage. But that Friday was nothing compared with what was about to unfold.

On the Saturday morning my head started to spin. Robert knew I had to take these pills and so he gave me the escitalopram and insisted I take it. At that point my vision started to blur and my auditory senses began to close down. My heart was pounding and I was sweating but soon I started to have a clarity of vision that was terrifying. I was filled with a certainty that today was my last day alive and that somehow God had ordained it. I was now convinced that my ex was part of a plot to poison me with the pill he had just fed me. I hallucinated that I had a knife and was stabbing myself in the stomach. What did happen was that I took a kitchen knife and lacerated the upper side of my left arm. By early evening the hallucinations took on a different tone. Now I was convinced I’d stabbed the children. I felt as if everything I was doing was being broadcast on national TV. I think but don’t know that I took another of the pills that evening.

[NOTE: Read more from Katinka Blackford Newman in a first person piece she wrote for MedShadow about how her experience with antidepressants has impacted her.]

Later my sister put me in the car and told me we were going to a private hospital in central London (we had health insurance). I still thought we were being filmed. On arrival, they asked me to sign a form saying I consented to taking any drugs. They sedated me and I fell into a deep sleep.

On September 23, 2012, I wake up in a small room in the hospital. I’ve got to get out of here, but I don’t know how. A nurse comes in with a pill and a glass of water on a tray. She tells me she’s giving me the pill that I have been taking — that the private psychiatrist gave me a few days ago. She insists I take the pill in front of her. A few moments after she’s left, I can feel my head starting to spin and my heart is palpitating again. There is a sort of whoosh that goes through my entire body, and I can feel my vision once more blurring and the colours in the room are getting brighter. Christ, I know there is something in that pill — I know it!

A doctor arrives. My first question to him is when can I leave? “Let’s see,” he says. He starts asking questions. For some time now, ever since that first pill of antidepressants , I seem to have lost the power of speech. My sister tells him how I’ve been going through a divorce, how recently I’ve started crying a lot, how I’ve been having sleepless nights, etc. I have great difficulty talking but I remember telling this doctor that somehow it felt like I had locked-in syndrome. Then I summon all of my willpower to express to him the reason I was there. “I’ve got a suicide pact with God,” I tell him. “So Robert can have the children.” Shocked, the doctor asks if I’ve been hearing voices. “Sort of,” I reply, before adding imploringly, “Can I leave soon?”

Today, Friday, October 12, 2012, I’m being discharged from the hospital. I should be happy, but I’m not. I’m properly ill now, but there are seeds of doubt in my mind. Yesterday, I’d googled the drugs I’m on. There it was, the side-effects: increased depression, anxiety, feelings of hopelessness. When the nurse came round, I refused to take the pills. One of the doctors was on the phone. “I’ve read up on the side-effects,” I said. “I think I’ve got them.” His voice was very stern: “You’ve been very ill with psychotic depression. You have to take those pills.” I was frightened. Scared he might not let me out if I refused to take them, then scared because maybe he knew best.

A few days earlier, I’d phoned Robert. I know I can’t look after the kids. My body is racked with involuntary movements. I can’t think straight. Would he move in while I get better? But I don’t get better. And this is why — because by now I really do have a chemical imbalance in my brain. It’s what experts have recognised as Prozac backlash — the brain’s reaction to intruding chemicals.

When a drug boosts serotonin in the brain, the brain’s chemical balance is upset. The result is artificially induced fluctuations not only of serotonin but also of the many other chemicals that act in concert with it. And that is why even if these drugs started out making you feel better than well, the end can be rather different. Because the result of this altered brain chemistry can be neurological damage and a whole host of side-effects including Parkinsonism, agitation, muscle spasm and tics.

By Christmastime I start to drink. I’ve never drunk more than a couple of glasses of wine before. Now I’m taking bottles of spirits to bed. Where was Santa Claus this year? I hadn’t been well enough to do their stockings. Lily and Oscar’s faces are etched with disappointment. Boxing Day — I’m on my own in bed with a bottle of whisky. My family organize a carer. They have to wash me and get me dressed.

By March 2013 I can’t bear to see the children’s hatred for me so I move out to a flat down the road. I’ve started smoking 70 cigarettes a day. The children cry when they have to visit. They ring Robert, begging him to pick them up. Oscar cries when I go to his sports day. He tries to pretend the woman dribbling and chain-smoking is not his mother.

By the end of August I want to kill myself. I know I’ve still got the kids, but I’ve lost everything. Because I can no longer feel and most importantly I can no longer love. I’ve ceased to be human. In September, I tell a doctor I want to kill myself, and I am sectioned at my local NHS mental health unit, St Charles Hospital. They take me off the drugs. Not just one, the whole lot. I start shaking. I’m now lying on the floor, writhing in agony. I can’t sleep, eat, think, anything. I start scratching myself uncontrollably. I start to hallucinate. Later I learnt that coming off one of antidepressants is supposed to be as bad as withdrawing from heroin. I was coming off five.

On Saturday, October 19, I was better. How do I know? Because Lily and Oscar said so. It was my birthday and I was allowed out to have dinner with the family. When I saw my son I drew him into my arms, smelling, touching, stroking and drinking up the smell, touch, sound, sight of my little boy now 11 years old. And for the first time in a year I felt the warmth of tears of joy running down my cheeks. Mummy was back.

What the hell happened? It doesn’t take long for my brain, now free from the damage of the drugs, to work it out. I find out about the charity RxISK, which has a website and publicizes the dangers of antidepressants. It’s teeming with stories like mine. It wasn’t me going nuts, the drugs had caused it. And I soon learn it’s happened to people all around the world; most have killed themselves or others.

It’s hard to describe what it was really like recovering from antidepressants. Once the tears began, they wouldn’t stop. The most important thing was looking into Lily and Oscar’s eyes and feeling love for them again. We began a very special love affair, born out of that year when I was stolen from them. When I left St Charles Hospital in November 2013, I vowed never to take another psychiatric medication again. The doctors told me to take the antidepressants like venlafaxine for a year. I chucked it away.

Copyright 2016, Katinka Blackford Newman.