Several years ago a senior named Sally Bell, started noticing weakness and achiness in her legs. “Maybe I’m not working out enough,” she thought. But then again, perhaps something else was wrong. “Yes, I’m older and I’m more sedentary than I used to be, but I’m not that out of shape,” says Bell. Finally, she talked to her doctor. That’s when she realized she was experiencing side effects from the statin drug she’d started taking. She stopped the drug and saw an almost immediate improvement. But even today, some of the damage remains.

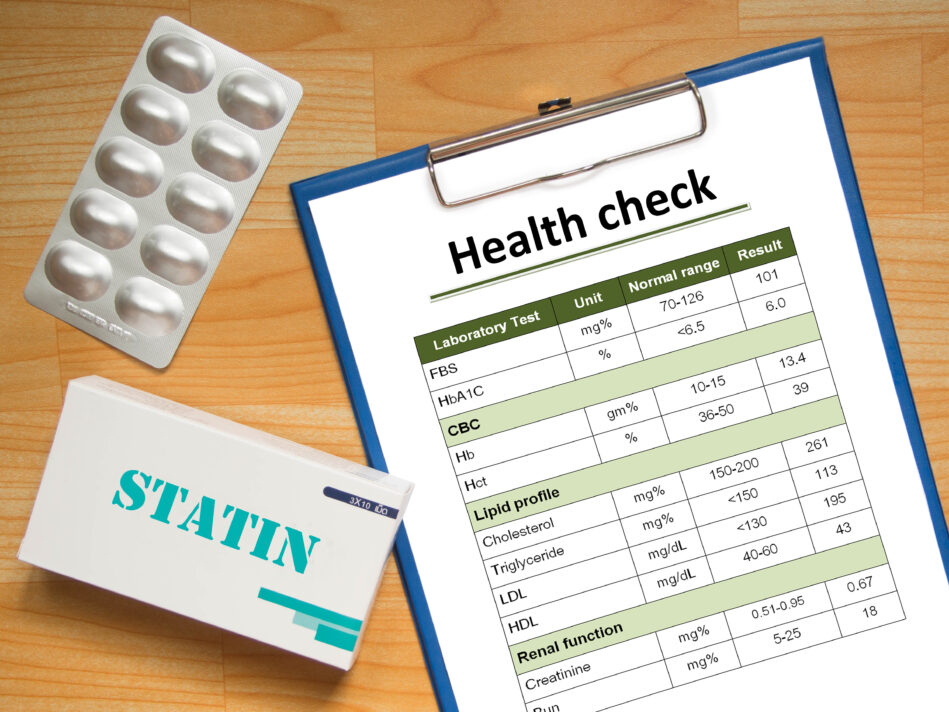

Bell was one of the millions of Americans prescribed a daily statin. More than one-quarter of all U.S. adults 40 and over — and nearly 50 percent of people over 65 — now take one of these medications, which lower “bad” LDL cholesterol and also tamp down body-wide inflammation, a major factor in heart disease and other chronic conditions such as cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

When statins first gained popularity for lowering cholesterol, doctors joked about putting them in the water supply. Now, despite the fact that statins are among the most-prescribed drugs in America (Lipitor currently tops the sales charts), guidelines from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) could greatly expand the number of people taking them. However, some doctors are criticizing the more aggressive position, citing concerns about side effects and the efficacy of the medications.

The USPSTF is now recommending that adults aged 40 to 75 should be put on a low-to-moderate dose of a statin — even if they have no history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) — if they have one or more risk factors for the disease and a 10% or greater risk of a heart attack or stroke within the next 10 years as a result. These risk factors include high cholesterol, high blood pressure, smoking, and diabetes.

The USPSTF, which is an independent group of doctors and health experts though commissioned by the government, also said that the risk of side effects or adverse events in this population from using a low-to-medium statin dose is small.

However, in an accompanying viewpoint, two prominent physicians expressed concerns with the recommendations, finding that the risks of statins in people at lower risk of CVD may outweigh the benefits.

“Although reported rates of adverse events in clinical trials are low, this does not reflect the experience of clinicians who see patients who are taking statins,” wrote Rita Redberg, MD, a cardiologist at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, and Mitchell Katz, MD, president and chief executive officer of NYC Health + Hospitals, the largest municipal health system in the United States.

Statins have been associated with a host of side effects. Based on observational studies, as many as 30% of those taking the medications experience muscle aches and pains. There is also some evidence statins may boost the risk of developing diabetes.

Redberg and Katz also expressed concern that broadening the scope of people recommended for statins might give them a false sense of security when it comes to protecting against CVD.

“For example, people taking statins are more likely to become obese and more sedentary over time than nonstatin users, likely because these people mistakenly think they do not need to eat a healthy diet and exercise as they can just take a pill to give them the same benefit.”

So, like all medications, statins are not without risks. Many people who take them stop, often because of side effects. As researchers from the UC Davis School of Medicine point out, based on a large body of evidence, adopting a healthy diet, exercising, and maintaining a healthy weight are the cornerstone in managing high cholesterol. And in their 2018 guidelines on managing cholesterol to reduce the risk of heart disease, the number one take-home message from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Task Force is that a heart-healthy lifestyle reduces heart disease risk at all ages.

Who Should Take Statins

Statins were originally designed to prevent second heart attacks in people with heart disease, and they do that job well. “Men and women with established heart disease benefit equally from statin therapy,” says Nieca Goldberg, MD, medical director of the Joan H. Tisch Center for Women’s Health at NYU Langone Health in New York City.

Doctors also use statins to prevent first heart attacks and strokes in people deemed at increased risk. The drugs can benefit men and women with high LDL cholesterol — and also those with normal cholesterol but high levels of an inflammation marker known as C-reactive protein, or CRP, measured by the high-sensitivity CRP test. “The Jupiter trial showed that healthy men 50 and over and healthy women 60 and over who have normal cholesterol and a high-sensitivity CRP score of greater than or equal to 2 mg/L reduced the risk for a first heart attack more than 30 percent” when taking a statin, says Dr. Goldberg.

The new ACC/AHA treatment guidelines state that anyone with a very high LDL (“bad” cholesterol) level — 190 mg/dL or higher — and anyone with a 7.5 percent or greater chance of having a heart attack or stroke or developing other forms of cardiovascular disease in the next 10 years, as indicated by an online risk calculator, should be prescribed a statin. Anyone with diabetes and an LDL of 70 mg/dL or higher should also be prescribed a statin, according to the guidelines.

A Changing Safety Profile

As far as prescription medications go, statins are considered relatively safe and effective — and yet, 40% to 75% of all people who start taking a statin stop within two years, and many patients have reported that they stopped taking the drugs within six months to a year. Side effects, commonly muscle pain, fear of liver damage, diabetes, or cognitive changes including forgetfulness and fuzzy thinking are catalysts for stopping the medicine. But according to a study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, people who stopped taking statins because of side effects were found to be slightly more likely to die or have a heart attack or stroke. The study found that people who continued with statins despite side effects had slightly better outcomes.

The research team analyzed whether people who continued taking statins ended up with better outcomes compared to those who abruptly stopped taking the drugs. Data were drawn from two Boston hospitals between 2000 and 2011.

Of the more than 200,000 adults whose data was studied, nearly 26,266 reported a side effect they thought might be related to the medication (usually muscle aches or stomach pain). Of those 26,266 the majority — 19,989 individuals — kept taking statins anyway. Approximately four years after the side effects were reported, 3,677 patients had died or suffered a heart attack or stroke.

Among those who continued taking statins, 12.2% fell into that group, compared to 13.9% of those who stopped statins after a possible side effect.

Additionally, the researchers found that 26.5% of patients who switched to a different statin again experienced side effects, but 84.2% continued taking the medication anyway.

According to a study on statin safety and side effects, from the American Heart Association (AHA), “no more than 1% of patients develop muscle symptoms that are likely caused by statin drugs.” And according to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved package insert that comes with simvastatin (which is similar for all statins), the risk of muscle problems is dose-related. In a clinical trial database in which 41,050 patients were treated with simvastatin with 24,747 (approximately 60%) treated for at least four years, the incidence of myopathy (muscle pain, tenderness or weakness) was approximately 0.02%, 0.08% and 0.53% at 20, 40 and 80 mg/day, respectively. Recently, in 2023, researchers started to find clues as to why some people who took statins had muscle aches and even severe weakness. It may be because the drugs interfere with an important enzyme. People with genetic mutations in this enzyme can develop a rare, but devastating type of muscular dystrophy.

CoQ-10, a supplement, was shown in a study to effectively decrease mild to moderate muscle pain in people who took statins. Fifty patients who reported muscle pain while taking statins participated in the trial. Half of the patients took a CoQ10 supplement and half took a placebo. Overall 75% of CoQ10 users experienced symptom improvement, with about a third of CoQ10 users experiencing a decrease in pain severity. Placebo users in the trial experienced no benefits (indicating actual effectiveness vs. a placebo effect).

However, studies on the benefits of CoQ10 for statin-associated muscle pain have yielded conflicting results. For example, a 2015 analysis of six studies including 302 patients receiving statins found no benefit of CoQ10 in improving muscle pain.

More recently, a review of 12 trials of CoQ10 with 575 patients found that CoQ10 supplements improved muscle symptoms, such as pain, weakness, muscle cramps, and muscle tiredness. Study authors, reporting in the Journal of the American Heart Association, note that the negative results of the 2015 analysis might be attributed to the limited number of studies and their small sample sizes.

David Katz, MD, director of Yale University’s Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center, recommends taking CoQ10 to treat or prevent muscle aches. “Most of my patients have done well with this,” says Dr. Katz. Talk to your doctor about whether you should try this supplement if you experience muscle symptoms while taking a statin.

Ironically, the excess rate of muscle-related side effects in people on statins may be attributable in part to the nocebo, or negative placebo, effect. In a study in the Lancet, participants aware that they were taking a statin reported muscle-related issues 41% more often than those who were not taking the drug. The catch is that in clinical trials of statins, the nocebo effect is quite high, says Dr. Katz. So in reality, many people who take statins have very real side effects, even though many of those side effects are due to the nocebo effect. (Read the MedShadow blog about the Nocebo Effect.) People who are at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes may increase that risk by taking a statin medication over the long term. Statins are also given to people thought to be susceptible to diabetes to help head off cardiovascular disease and to lower levels of fat in the bloodstream.

Researchers conducted a long-term follow-up study that looked at more than 3,200 patients who took part in the US Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study (DPPOS). That study examined whether losing weight through changes in lifestyle or taking the diabetes medication metformin could delay or lower the development of diabetes in high-risk individuals.

At the start of DPPOS, about 4% of participants were taking a statin. But after 10 years, nearly one-third of patients in the study were taking the drugs. The most commonly prescribed statins were Zocor (simvastatin) and Lipitor (atorvastatin).

Taking a statin was associated with a 36% higher risk of later being diagnosed with diabetes, no matter which treatment group patients had been in the study. Among women, the increase in risk is higher, says David Katz.

Despite this fact, many doctors believe the benefits outweigh the risks. A review in The Lancet makes this point and highlights the fact that side effects have been greatly exaggerated. The review concedes that serious side effects, including muscle pain or weakness and diabetes, can be caused by long-term statin use. But the number of people potentially impacted by these effects is quite small. For example, statin use may cause muscle pain or weakness in 50 to 100 patients per 10,000 treated for five years. The researchers also noted that the bad rap statins have been getting in recent years may have led to avoidable deaths in people who stopped taking statins as a result of negative press.

Liver damage is another potentially serious side effect. The FDA calls serious liver injury from statin use “rare,” to the tune of two or fewer cases per one million patients annually. A study in the journal Clinics in Liver Disease points out that it is common for people taking statins to have dose-related elevated liver enzymes, which could indicate liver damage. But enzyme levels in people taking statins were not consistently different than in people taking a placebo. Research shows that the risk of liver damage caused by statins is about 1%, similar to the risk in people taking a placebo. In fact, the FDA-approved package insert on Lipitor (atorvastatin) notes that in the drug’s clinical trials, the incidence of elevated liver enzymes occurred in less than 1% of patients unless they were on the highest dose, in which case it occurred in only about 2%. In a drug safety announcement, the FDA revised label requirements to remove the recommendation for people taking statins to undergo periodic liver monitoring. Doctors should test liver enzymes before starting a patient on statins, and perform follow up tests only if clinically indicated. Nonetheless, if you are concerned about liver problems or think you notice symptoms, talk to your doctor. Symptoms of liver disease include unusual fatigue, loss of appetite, pain in the right upper abdomen, dark urine, and yellowing of the skin or the whites of the eyes.

Certain people may be more prone to side effects from statins than others, says Dr. Goldberg. These include older people and those who take multiple medications, have a small body frame, use a calcium channel blocker (brand names include Norvasc and Cardizem), take antibiotics such as erythromycin or clarithromycin, or drink grapefruit juice, which increases the effects of atorvastatin, simvastatin, and lovastatin, but not pravastatin or rosuvastatin, says Dr. Goldberg. To minimize the risk of side effects, talk with your doctor about avoiding drugs and beverages that interact with your statin.

If you experience side effects while taking a statin, talk to your doctor right away. He or she may switch you to a different statin, which often helps, or lower your dose. Or you may need to go off your statin altogether.

“Sometimes we need to use non-statin cholesterol medications in people who have side effects,” says Dr. Goldberg. Several types are currently on the market including drugs that bind to bile acids in the intestine, those that block the formation of LDL, and those that block the absorption of cholesterol from food.

These other methods to lower cholesterol may be just as effective as statins in also reducing cardiovascular events. Researchers analyzed 49 trials involving more than 300,000 people that looked at different ways of lowering cholesterol. The trials were sorted into four groups: Those that examined statins; non-statin treatments that work to lower LDL cholesterol levels such as diet and the drug Zetia (ezetimibe); fibrates and niacin; and the newest class of cholesterol-lowering drugs known as PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9) inhibitor antibodies. Statins and non-statin interventions had similar reductions in the risk of a heart attack, stroke or need for a stent, according to the study, which was published in JAMA. Fibrates and niacin also worked to mitigate the risk, though the reduction was not as great as with statins and non-statin treatments. The PCSK9 inhibitors also showed some benefit.

The newest non-statin drug to be FDA approved for reducing LDL cholesterol is the PCSK9 inhibitor antibody Praluent (alirocumab). Along with diet, along with other cholesterol-lowering drugs, or alone, this injectable drug lowers LDL in people with inherited high cholesterol, or with cardiovascular disease.

A 2019 study published in JAMA tested an experimental non-statin drug called bempedoic acid in nearly 800 patients at high cardiovascular risk who were already taking maximally tolerated doses of statins and other lipid-lowering medications, but still had uncontrolled high cholesterol. Patients were given either a daily dose of bempedoic acid or a placebo in addition to their ongoing high-cholesterol therapies. After 12 weeks the bempedoic acid group experienced a 15.1% reduction in LDL cholesterol levels vs. a 2.4% increase in LDL in the placebo group.

In a safety and efficacy study published in 2019 in The New England Journal of Medicine, bempedoic acid added to maximally tolerated statin therapy lowered LDL cholesterol significantly without causing any more side effects than a placebo. After correcting for the effects of the placebo, bempedoic acid led to a 21.4% reduction in LDL cholesterol.

Research into understanding, diagnosing, and treating lipid disorders is ongoing.

Under-Prescribed or Over-Prescribed?

“Statins clearly save lives, and could save many more,” says David Katz. “People with dyslipidemia [high blood levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, or both] and excess inflammation stand to benefit. More than 635,000 people die of cardiac events each year in the U.S.; statins could reduce this toll substantially.” So in this sense, says Dr. Katz, statins may be under-prescribed.

And yet, if more people followed a heart-healthy lifestyle, many of them would not need the drugs. Dr. Katz, the author of Disease-Proof, believes that “if lifestyle were used as medicine, 80 percent of all heart disease could be eliminated, no prescription required.” He adds, “Using medication is not nearly as good, and yet we tend to neglect the power of lifestyle as medicine and rely on meds.”

Dr. Katz recommends losing extra weight, getting more exercise and following a healthy, mostly plant-based diet. One good choice is the Mediterranean diet, which includes plenty of fruits and vegetables as well as good-for-you fats from nuts, seeds, olives, avocados, and fish. (See MedShadow’s Stuck with Statins? Try a Plant-Based Diet to Cut Back.)

More from MedShadow: