The Pill – 60th Anniversary

As I write this, it is one day after the 60th anniversary of the first oral birth control that was approved for use in the United States. It was part of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and access to “The Pill,” as it was called, famously separated sex from procreation. “Oh pish posh,” you say, there were many types of contraceptives available for hundreds of years, maybe thousands.

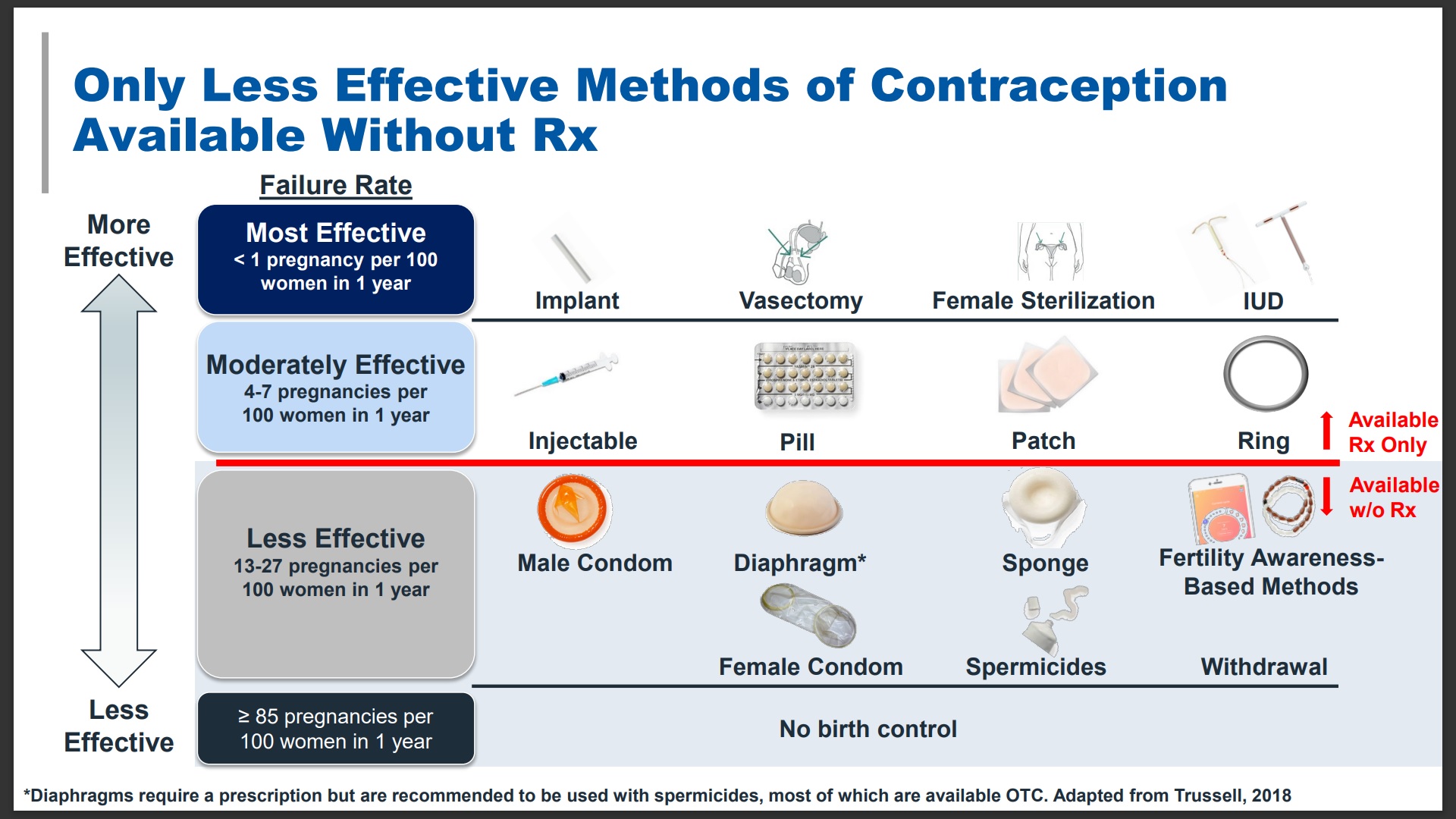

The Pill, however, was dramatically more effective than other birth control methods available until then. Here’s a diagram from Perrigo Company (manufacturer of OPill) illustrating that the birth control methods

available without a prescription are significantly less effective than those that require a prescription. Nearly half of all pregnancies in the U.S. are unintended.

Even more life changing, The Pill put women in sole control of contraception. All the other options at the time required the man to agree and participate: condoms, spermicide, withdrawal, family planning… A woman was at risk that her partner may not agree to use a condom or might promise to withdraw and then not. Women, even wives, were far from equal partners in intimacy because of the nine-month commitment of pregnancy.

I remember watching Susan Lucci’s character, Erica, on All My Children in the 1970s. Erica was secretly using birth control pills while her husband was anxiously awaiting her pregnancy. She kept telling him she wanted a career before having a baby, but he insisted she had to have a baby and wouldn’t use birth control. It was thrilling to see a woman exercise her power at that time – even if the power struggle over procreation was demolishing their marriage, and yes, it was a dramatic soap opera.

But, the pill did not fully deliver on its promise. If you can’t get it, it’s no good to and some women still cannot get it because it requires a prescription. To get a prescription, a woman has to have a personal doctor or wait to see a stranger in a clinic. Often, a non-emergency appointment can take a month or more to schedule. Women who work may not be able to make appointments during daytime office hours. They may have limited sick days or time off and can’t afford (or won’t be allowed) to take unpaid time off.

Transportation could be an issue for any woman. There are women who live in healthcare deserts, who have to drive more than an hour just to meet with a doctor. Women with childcare responsibilities also may have a lot of difficulty matching their schedule to the health system’s day-only appointments. Going to a clinic might include an unpredictable multi-hour wait. Health appointments may cost money or a copay, as might also the prescription for the pill itself. Not everyone has health insurance, and not all health insurance plans pay for contraceptives. (No feminist – and yes, I’m a feminist – can let that last fact roll by without pointing out that Viagra, a drug that helps men with erections, is routinely covered by health insurance.)

To add to the challenge, this complicated process must be repeated annually in order to have the prescription renewed. About one-third of all women who use oral contraceptives report that they have had trouble getting the prescription or getting it refilled on time. This struggle may in part account for the fact that 50% of all women in the U.S. will experience an unintended pregnancy by the age of 45.

Among 15- to 17-year-olds in the United States, 72% of pregnancies were unintended. Yet adolescents face even more barriers – parents who refuse to allow them to get prescription birth control, so the teen must find a way to reach a doctor and fill a monthly prescription without the help of parents or insurance. Teens may not have transportation to get to health appointments. Two teens who testified in the recent FDA Advisory Committee who asked their pediatrician for a prescription for contraception were refused because the doctor believed that the teen should not be engaging in sex. Judging a teen does not stop sexual activity.

When I got the email asking me to sit in as a Consumer Rep on the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) Advisory Committee meeting that would ask my opinion if an oral contraceptive called OPill (a progestin-only mini pill) could be offered over-the-counter (OTC) instead of as a prescription, as all oral contraceptives currently are in our country, I said, “Would I?!”

The idea of a woman being able to walk into a drugstore, select the birth control method that is best for her needs, and walk out with it, all at one visit, is mind-blowing.

In preparing for the FDA meeting, I needed to learn about progestin-only mini pills. In reviewing the pre-meeting documents from the FDA and from the sponsoring company, Perrigo Company who manufactures and sells OPill, I was reassured. The OPill was originally named Ovrette (norgestrel) and approved by the FDA in October 1973. The owner of Ovrette stopped promoting it in 2005 due to low sales, but there were no safety issues. It was acquired by Perrigo Company four years ago with the intent of requesting the FDA to move it from a prescription to an OTC drug.

The OPill (and all mini pills) has been on the market long enough to have historical proof of safety. It has few well-known side effects (bleeding changes and spotting are the most common) and few contraindications (health reasons why a woman should not take it). The only group of women who definitely should not take a mini pill are those who have or have had breast cancer (as these cancers can be stimulated by progestin).

Mini pills become effective in only two days, because in addition to suppressing and interrupting ovulation, it thins the lining of the uterus making it difficult for an egg to implant, and it thickens the cervical mucus, making a barrier for the sperm to get to the egg. The pills have such a low dose that it is pretty much impossible to take enough for them to become toxic in your body.

The FDA seemed as satisfied with the science as I was. The FDA always creates a list of questions and votes that they want the Advisory Committee to discuss. For Opill, all of the questions focused on if the manufacturer had shown that the packaging alone could communicate to women how to determine if it was a good choice for them, if the few women who should not use it for health reason can identify that, how to use the contraception, and what to do if one of the daily pills is missed.

During the nearly two-day Advisory Committee meeting, we reviewed the five comprehension studies that were submitted by the sponsoring manufacturer to the FDA. The good news was the sponsoring company was able to show upbeat results from the study for the key metrics, which were the same as the FDA discussion questions. The studies showed 90+% comprehension of “take a pill every day at the same time” and “if you miss a pill, keep taking them but either avoid sex or use a barrier method for two days,” and “don’t use if you have or have had breast cancer” directions.

The comprehension levels for adolescents and those of low literacy were slightly lower, but acceptable to the FDA. The committee discussed the issue of “don’t use it if you have or have had breast cancer.” A breast cancer specialist on the panel explained that she wasn’t too concerned about adolescents/low literacy having low comprehension because almost no adolescents have breast cancer and, importantly, a woman who has or has had breast cancer is almost certainly under the care of a doctor with whom she can easily consult about her contraceptive choices.

The secondary level of questions tested the understanding of topics like, “what to do if you miss taking a pill one day,” “what to do about breakthrough bleeding between periods,” etc. Understanding did not achieve levels as high as the primary level, but again were 85+% for the general study participants. However, in looking at the subgroups of adolescents and low literacy, the comprehension numbers dropped into the 60 to 80% range. Those looked like worrisome results, and the FDA had highlighted this as an issue.

I asked the FDA, how did those results compare to the women who received a prescription for a mini pill by doctors? The answer? The FDA doesn’t know.

The FDA has never asked for or required a similar study for prescription oral contraception patient understanding of how to use the drug. There is no way to compare how well women understand the directions from the package as compared to receiving the directions from the doctor.

It might seem obvious that being told something means you’d have a better understanding over reading something, but that’s not always the case. Doctor appointments last 20 minutes on average and in that time the doctor must find out the reason or reasons for the visit, gather the history, diagnose, prescribe, explain the diagnosis, and what care the woman can expect. Not all patients are comfortable asking follow-up questions or pushing back if she doesn’t understand. Well-designed packaging might increase understanding for any medication.

The most controversial study presented in the FDA meeting was called “ACCESS.” Part of this study required women to track if and when they took the pill in an electric diary. That part of the study was very hard to design, and the results were not very useful. The key issue is that about 30% of the women entered into the diaries saying that they had taken more pills than the FDA had supplied. This threw doubt on the value of any of the information in the study. The FDA suggested that the Advisory Committee consider voting against moving the pill to OTC distribution until and unless the sponsoring company re-did the research with data they could trust.

I asked the FDA if there were any studies tracking if women who had been prescribed the pill were more successful at taking it daily at the proper time. The FDA acknowledged that it had never been studied. And I challenged the FDA that, without knowing how many of the prescribed women took the pill correctly, we did not know if the OTC group did better or worse. Re-doing the study on OTC pill taking women would never be useful unless we had a parallel study on women prescribed the pill.

In discussion, it became clear that the Advisory Committee, for a variety of reasons, did not feel the failure of ACCESS to show a clear success was a reason to not approve Opill for OTC distribution.

For the majority of the Advisory Committee members, and for me, it came down to assessing the greater harm, leaving in place the barriers to accessing oral contraception for all women (but especially for teens), or allow the pill to be available to all women, knowing that some women who choose the product will make errors while using it.

I voted in favor of allowing OPill to be sold OTC, as did all 16 of the other members of the Advisory Committee. It was unanimous. Members of the Committee are always asked to explain why he or she voted for or against the drug. Here were my comments (edited for clarity).

I support having sponsoring companies meet or exceed the standards set by the FDA. However, that often doesn’t happen in these Advisory Committees because of mitigating circumstances.

The women in the study showed that they could select the pill or choose to deselect accurately. The areas in which the research seems particularly short are having to do with actual use after purchase. I say it seems short because we have no research to which we can compare the data. We have no proof that women receive complete counseling when prescribed the pill or that they are in a situation where they feel comfortable asking questions. We have no way of knowing if they are better or worse in actual use, as we cannot compare those prescribed versus those potentially purchasing OTC.

Dr. Anna Glasier, MD, Dsc, OBE, Professor at Edinburgh and London Universities, representing the sponsoring company, offered two studies based in Europe that support imperfect compliance in those women who were prescribed oral contraceptives by doctors, even with reminders.

We also know mistakes are made by women taking the prescribed pill because there are a lot more unintended pregnancies than expected if contraceptives were consistently used appropriately.

The FDA stated that because 30% of the respondents in the sponsor’s ACCESS study reported that they took more pills than was possible, that part of the study was not usable, and we should consider if the entire study should not be used. Even if we had perfect data showing how women took an OTC medication, we didn’t have any comparison data. Without a baseline comparison of prescription use compared to OTC drug use, the study didn’t tell us anything.

I believe this is a mitigating factor and a reason that the uncertain results of the ACCESS study should not impede approval.

Reasonable access to effective contraception is the most important issue. I was struck by the sponsor’s chart on OTC birth control methods versus prescription options. The methods available OTC are less effective, need participation by both partners, and, frankly, also need explanation and even practice to use appropriately. The Opill use instructions are no more difficult to understand and apply than the products presently available OTC. And, the Opill is much more effective.

Pregnancy is a dangerous physical risk in America and should be a choice, not a trap. Maternal deaths have nearly doubled from 2018 to 2021. Progestin mini pills are much more effective than other products already offered OTC. More women are likely to be harmed by an unplanned and unwanted pregnancy than any negative impact of Opill. Again, I vote to approve the move to OTC access.