Last week, the FDA approved yet another direct-to-consumer pharmacogenetic test. This one will help determine how your body metabolizes medications based on genetic variants. Do you need it?

The short answer is no.

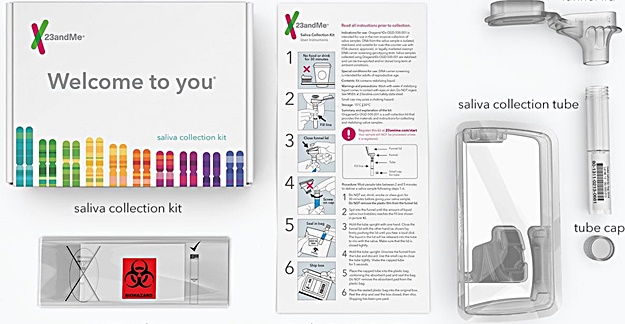

The test, from 23andMe, analyzes a saliva sample and based on 33 genetic variants can predict how that person will metabolize medications. That’s it. It can’t predict how a person will respond to a particular drug, a finding that would be quite useful.

So why is knowing how you metabolize a drug important at all? A drug metabolization rate can influence a drug’s efficacy and side effects. Yet, 23andMe admits that the test only predicts whether a person is a slow or fast metabolizer of medications in general. It doesn’t provide any information on, say, if a person is a slow metabolizer, how that should influence prescribing of a drug.

With this in mind, what is the usefulness of this test for the consumer? It appears to be quite limited. Even the FDA admitted as much. “This test… does not determine whether a medication is appropriate for a patient, does not provide medical advice and does not diagnose any health conditions,” Tim Stenzel, director of the FDA’s Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health, said in a statement. He added that consumers should not use results from the test to make treatment decisions – such as stopping a medication – on their own, but undoubtedly many of them will.

The Genetic Tests Could Lead to… Another Test

The idea is that patients would take the test results to their doctors for further discussion. Yet even then the utility of the test appears limited. “Healthcare providers should not use the test to make any treatment decisions,” the FDA said. “Results from this test should be confirmed with independent pharmacogenetic testing before making any medical decisions.”

In other words, after getting the 23andMe test and showing them to your doctor, you will need even more testing before any decisions are made on medication changes.

There’s been a recent proliferation of pharmacogenomic testing that has become available. Many of them tout their ability to predict a person’s response to certain medications, allowing doctors to select the most appropriate drug for a patient. Yet, despite heavy marketing, the tests may not be backed up by appropriate scientific or clinical evidence.

Perhaps that’s why a day after the the approval of the 23andMe test, the FDA issued a warning that many such genetic test claims have not been substantiated by the agency. The FDA also noted that “selecting or changing drug treatment based on the results from insufficiently substantiated genetic tests… could lead to potentially serious health consequences for patients.”

I look forward to the day when a genetic test can actually help determine the best medication for a patient for a given condition. But we’re not quite there yet. Until then, understand that many of these tests have limited benefit to patients and are often nothing more than a waste of money.